The Monk

It is just one man’s downfall, not mankind’s. Hardly apocalyptic, and it hardly seems worth all the fuss.

Plot summary

Abandoned as a baby on the steps of a monastery and raised in strict Capuchin fashion, Ambrosio has become the most famous preacher in the country. While large crowds from all over the country come to hear his mesmerizing sermons, he’s also bitterly envied for his success by certain fellow monks.

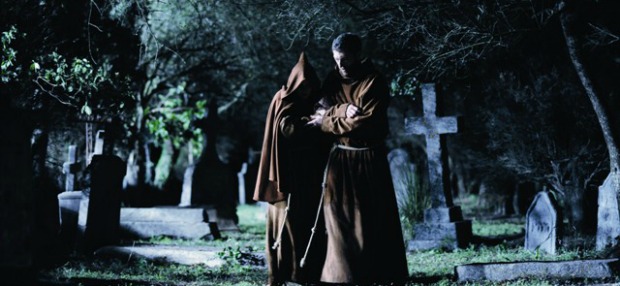

Lightning rents the black sky. A castle, er, monastery sits high and forbidding on a distant hill. Eddies swirl in angry, bloated streams; foundlings are dangled. Crows screech from turrets; gargoyles loom with hollow mouths.

The Monk, the new film by Dominik Moll (Lemming; Harry, He’s Here To Help) has all the tropes of a sturdy diabolic horror film: thrashings of Hammer gothic, buckets of Roger Corman Grand Guignol, and also—as a bonus, because it’s French—nods to Bosch, Breugel, Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc and Jodorowsky’s daylight surrealism.

Brother Ambrosio (Vincent Cassel), an orphan left on the steps of a monastery in Spain, is a charismatic spewer of brimstone. The faithful come from miles to hear him preach, and young maidens swoon at his vigor. He is a superstar for Jesus, with all the swagger that makes a celebrity irresistible, though for a man who’s taken the oath of the Capuchin order it’s perilously dangerous (and makes him guilty of at least two deadly sins and perhaps three commandments). But evil is lurking, as we’re told repeatedly. When a mysterious acolyte appears in a mask to hide his fire-ravaged face, things, of course, are not what they seem. And when a nun with quivering knees and a face out of a Van Eyck painting gets nothing from Brother Ambrosio but pompous and merciless penance, the tripwires of vengeance, temptation, and hubris are laid.

Based on a book of ‘sulphurous reputation,’ as Moll puts it, The Monk was originally published in 1796, written in ten weeks by a 19-year-old named Matthew Gregory Lewis for—allegedly—the entertainment of his mother (a lewd novel about incest and matricide—Happy Mother’s Day!). It was shocking at the time, blasphemous, immoral, and even Coleridge (a bit louche himself) remarked, ‘if a parent saw The Monk in the hands of a son or daughter, he might reasonably turn pale.’ The Marquis de Sade was a fan, and the surrealists embraced it: André Breton wrote, ‘It is infused throughout with the presence of the marvelous,’ Antonin Artaud wanted to turn it into a film starring himself, and Luis Bunuel actually did adapt it into a screenplay, filmed in 1972 by Ado Kyrou. A fine pedigree of salaciousness, but what could make a matron reach for the smelling salts in 1796 seems comparatively chaste to us now, a generation that has lived through The Exorcist, Deep Throat, and Irreversible.

It is a beautifully toned piece of work, and wonderfully unsubtle: Moll uses self-consciously old-fashioned effects, like iris transitions and double exposures (cue hellfire, cut to hellfire—actual hellfire) and almost parodic montage (after two young suitors meet, he cuts to a bee rabidly pollinating a lurid flower; I suppose seeing a train going into a tunnel would have been anachronistic). It is also easily one of Cassel’s most complex and brilliantly constructed performances. When Brother Ambrosio gets a whiff of female delights, Cassel is stupefied yet driven like a puppy in rut: holy, mad, confounded, all at the same time—‘very quickly he gave a name to the acting style I directed him to do,’ Moll says, ‘German-Japanese minimalism!’ That Cassel succeeds in making a recitation of the sixth psalm more erotic than the Penthouse Letters column is remarkable.

But the film is all foreplay. Or it’s all the right foreplay but the wrong movie. Or the right movie but the wrong foreplay. What it isn’t is what it teases it will be. It is not a gothic horror, or one of those sinister popery films with sly monks and naughty nuns, movies like Ken Russell’s nutloaf The Devils or Jerzy Kawalerowicz breathtaking 1961 film, Mother Joan and the Angels, both of which The Monk echoes (because basically they’re the same film, really, with different degrees of artistry and sanity). What it is is the kind of film that France does best, an intimate character study of complex emotions, duty, passion, sensuality (there’s a reason repressed countries make better horror movies). Sure, there’s falling masonry, bells tolling whenever anyone says something ponderous, and some crawling around inside graves by moonlight, but after a while we wonder, is the devil coming or what? All it boils down to is lust, really, and as such probably not a good idea for a monk. And, sure, it gets a little complicated (quite a bit more complicated). But it’s still just lust; the monster unleashed is only too human.

The devil is—as Mel Gibson, that sage of theological cinematism, knew—a woman. That’s also how Von Trier provoked us in Antichrist—male fear and hysteria over the mystery of women’s sexuality, womanness as chaos, something to be feared, something certainly anathema to the Holy Roman See. But it is just one man’s downfall, not mankind’s. Hardly apocalyptic, and it hardly seems worth all the fuss.

COMMENTS