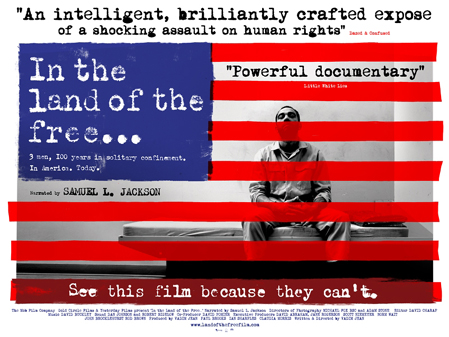

In The Land Of The Free

Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox and Robert King were strangers when jailed in the 1970s. A conviction for the murder of a prison guard and decades in solitary confinement now unite them as The Angola Three.

Plot summary

Tells the story of Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox and Robert King, three black men from rural Louisiana who were held in solitary confinement in the biggest prison in the U.S., an 18,000-acre former slave plantation known as Angola.

Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox and Robert King were strangers when jailed in the 1970s. A conviction for the murder of a prison guard and decades in solitary confinement now unite them as The Angola Three. King, released in 2001, spent 31 years in Louisiana State Penitentiary (also known as Angola) while Wallace and Woodfox remain there after 37. This documentary attempts to expose their continued mistreatment as a violation of their rights and a miscarriage of justice. It is clearly a labour of love and the film’s dedication to Anita Roddick hints at the philanthropy and moral action at its heart.

Looking afresh in 2010, the situation that director Vadim Jean paints is staggeringly straightforward. These men should not be in jail. Decades of prejudice, discrimination and corruption driven by institutional racism and fear have stolen their lives. Rarely did I suspect that the moral balance was distorted as the facts of the story and its rich array of characters are allowed to speak for themselves.

The film doesn’t ignore their youthful criminality and in their own recollection it comes across as charmingly nefarious. Armed robbery amongst other misdemeanours is passed over like everyday adolescent mischief. Tales like a prison escape and fleeing to the magnetism of Harlem in a cement truck make the image of petty rogues hard to resist. This anecdote segues into a rare moment of sentimentality and a vision of the vibrant cultural and social upheaval these men would not see. Those lost decades also bore witness to stagnant race relations in Louisiana and the undertones of subjugation and its echoes of slavery ultimately prove to be more current than symbolic.

All three became members of the Black Panther Party in Angola when politicised inmates led unprecedented change. The population were desegregated and the routine rape of new inmates was eradicated. Some prisoners were motivated to study law and became experts on their rights and conditions. For the prison hierarchy, in spite of its positive effects, mass organisation meant the potential for mass revolt. Policies were drawn up to neutralise the party. As paranoia and fear of Black Panther activism grew in the outside world, tensions in Angola were magnified. Like victims of a virus, leaders were quarantined in the hope that other prisoners wouldn’t become infected. When this only incubated the problem it seems that the authorities wanted an excuse to put three of the party in solitary confinement. With the murder of prison guard Brent Miller they found one.

The film uses an ironic impartiality to present every character and perspective. Each new voice is introduced with complete credulity and at different points it feels like prosecution testimony might reach a critical mass. But the house of cards that is the case against them is gleefully nudged. This faithful depiction of the evidence begs the question, how did such a disparate mess of ineptitude disguise the truth?

Some of the absurdities are handled in a way that doesn’t overplay their tragedy but actually leavens the mood. There are real notes of, hopefully intentional, comedy. For one key witness, revealed as a malleable cog in the grand conspiracy, there is only one archive photo: black and white, all gnarled and bemused. He was bribed with cigarettes and, in spite of his violent crimes, promised freedom if he would testify. As the clichéd dynamics of his situation are drawn out we repeatedly revisit the same single slow zoom shot. With each repetition more bizarre facts are revealed and he looks less threatening and more ridiculous, slowly transforming into a sepia-tinged clownish ghost. Somehow this was genuinely funny.

Equally ridiculous and similarly tailored to the absurd is the account of another key witness. Once again his testimony is for a while presented as reasonable. Then we learn that the consistency of key elements makes them either physically implausible or psychologically ridiculous. The narrative then shifts the focus of our reflection. The shocking frailty of the case; the notion that this frailty was an artifice of rubbish lies; and finally the punchline: The key witness, the crucial element of this slapdash fabrication was a “legally blind, mentally retarded sociopath.”

This scattered irreverence works because the spirit and humour needed for the telling are so strongly evident in its subjects. Their humour survives and, as in good satire, tragic follies are reframed to deflate their terrible force and offer hope and revenge in laughter.

One problem with the film is that the visible villains, clown ghost and blind guy among them, are only bystanders. Pawns as targets for indignation just won’t do. Institutional corruption is good at hiding its face but the bad people at the core of this case cannot be that well hidden. In spite of this significant absence, In the Land of the Free still succeeds as a gripping moral appeal. It is well paced, skilfully shot, deeply evocative, and a comprehensive story well told. Most striking is its enduring sense of hope and defiance. When a man speaks of the joys of a windowed cell and seeing the moon’s palliative beauty for the first time in years, I suppose it’s hard not to follow suit.

COMMENTS