When is a Film Score Not a Film Score?

Having written a fair amount about film music, I am often asked which score is my favourite. It’s not that it’s a tiresome question, but I tend to want to give an oblique rather than clear and obvious answer: my favourite ‘film score’ is not for a film at all, indeed, it has no moving image counterpart, and was written by someone who does not consider themselves a ‘musician‘. This confounds people, and their confusion is not dispelled when I tell them that it is Nicholas Briggs’s score for the Doctor Who audio adventure Sword of Orion. This is one of a series of what are in effect radio plays released only on CD and made by an independent company called Big Finish. One reason why I might call the music a film score is that it exhibits most of the characteristics of a film score, although music for radio is a not-too-distant relation of music for films. In aesthetic terms, it could have been a film score. Indeed they could have added images to it like the vast majority of animated films begin with a soundtrack to which images are added.

The Big Finish Doctor Who audios were the culmination of an historical process. Doctor Who began as a television programme produced by the BBC in 1963 and immediately inspired a fanatical following. By the 1980s, the programme was deemed out-of-date and was cancelled in 1989. The fans of the show not only campaigned to have it returned to the television screen but also began to make their own Doctor Who products. Apart from a proliferation of fanzines and novels, some audio plays were written and recorded, only gaining minimal distribution through fan networks. One of these early amateur audio plays was Sword of Orion written by Nicholas Briggs, which, once Big Finish had established their series of audio play CDs, was dusted down and reformulated for the series. It should be noted that while Doctor Who, nominally at least, primarily was a children’s programme, it always had a strong adult following. With its cancellation, the children who loved the show grew into adulthood and the audio plays reflect this in being aimed firmly at a more mature audience. Indeed, with Doctor Who‘s return to television in 2005, the audio plays seemed more of the character of its more ‘adult’ oriented spin-off sibling Torchwood.

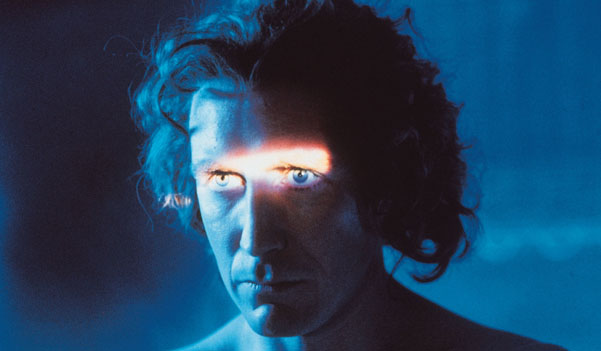

Doctor Who: Sword of Orion (Big Finish, 2001) was a four-part audio play written and directed by Nick Briggs (who also provided the voice of the cyberman). It starred Paul McGann as the Doctor and India Fisher as Charley, his companion. Sword of Orion is about a salvaging crew towing away a large spaceship to find out that far from being empty it is filled with slowly-reviving cybermen (emotionless ‘robot’ beings who have replaced their humanoid flesh with metal machine). The Big Finish audios almost take place in a parallel universe to the television serial, righting a few wrongs in Doctor Who. Paul McGann has a run of adventures that he was denied by the ‘failure’ of the attempt to revive the serial with the Doctor Who TV movie in 1996, in which he starred. Its British viewing figures were pretty much the same as those for the triumphal return of the Doctor Who TV series helmed by Russell T. Davies and starring Christopher Eccleston in 2005. The ‘failure’ was in its lack of hooking US syndication. So much for the BBC as a public service for Britain. The Big Finish audios also allowed another earlier Doctor, Colin Baker, an extended run to make up for his disappointing tenure at a time when the BBC had lost interest in the programme. Both have excelled and their vocal performances have sustained the number of stories featuring both from the late 1990s to the present. That the music for the Big Finish audio adventures is considered an essential and notable part of the stories is evident from the release of Briggs’s score, along with others, on CD.

Briggs’s music takes its lead from a number of sources. According to his CD sleeve notes, one is Jim Mortimore’s music for the original fan audio play, for which Briggs contributed a 10-note theme that forms the basis of this score. It also takes inspiration from the musical component of cybermen appearances in earlier television Doctor Who stories (most notably Tomb of the Cybermen (1967), Revenge of the Cybermen (1975) and Earthshock (1982)). Sword of Orion’s music has little in the way of memorable melodies and, at least on first listens, and contains little in the way of traditional music. It consists solely of synthetic sounds, although it uses recognizable orchestral timbres (in their strange ersatz electronic versions), dominated by echoing percussion and brass sounds (referencing the library music used in Tomb of the Cybermen) and haunting French horn sounds (reminiscent of some musical passages in Revenge of the Cybermen). Initially it sounds chaotic, appearing to avoid tonal organization, and using cells of melodic line rather than tunes and themes as such. There are repeated and developed musical figures but these do not plainly follow any musical logic, or indeed any audiovisual logic through connecting as themes for characters and situations. Perhaps the main reason for the seemingly chaotic mélange of musical sound is the persistent and prodigious use of echo. Not simply a slight return and reverb but massive build-ups of repeated slapback echo, as if the music were taking place in the largest canyon imaginable.

Broadly, it seems to be divided between quiet, atmospheric angular melodies and a jamboree of echoed percussion and synthesizers for the more exciting sections. The sounds are wonderful and characteristic of 1970s synthesizers, which had a distinctive sound which was bolstered by their extensive use on science fiction TV programmes. It should be noted that the work of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, which produced electronic music and sound for radio and television but most notably for the Doctor Who television serial, increasingly is seen as a crucial body in British experimental music – despite its position at the heart of mainstream British culture. It not only encouraged experimentation but also provided popular outlets for the sonic productions of its members. During the 1960s and 1970s, it provided the ‘special sound’ for Doctor Who and sometimes the musical score, while at the turn of the 1980s it became the sole provider of music for the programme. This offered an opportunity for sound effects and music to be integrated in a manner similar to the feted sound designs of recent Hollywood cinema. Such electronic sound/music has become oddly reassuring to Generation X-ers who grew up with such bizarre sounds in Doctor Who or Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1981). The Big Finish productions derive some of their sonic direction from this point, with Alistair Lock sound designing many of the CDs and sometimes providing the music, too.

The Doctor Who theme, which had been iconic since the title sequence of the first programme in 1963, was rearranged for this run of Big Finish audios by film composer David Arnold, who is best known for providing the recent scores for the James Bond series of films. Although essentially radio plays, there is a certain cinematic dimension to some of these audio adventures, not least in attempts to create a large canvas for philosophical themes rather than keep them as modest chamber pieces. Music plays a crucial role in this. Composer Nicholas Briggs writes in the sleeve notes to the CD:

My main aim with Sword‘s music was to create a cinematic feel. TV and radio music tends to be far more economical, punctuating and supporting the drama whereas film scores on a grand scale often drive the story’s emotional centre, foreshadowing terrifying events to come. With Sword of Orion I wanted to say, right from the opening scene, ‘Something wicked this way comes’.

In the sleeve notes to the audio adventure itself he states: “… the only on-screen template for these new adventures was cinematic in nature.” The music certainly sounds ‘big’, although not gargantuan in the crass manner aimed at by many mainstream orchestral film scores. (Musical bluster makes films seem important and can misdirect you from their sloppy aspects.) While the music may be synthetic, computer music, it manages a complexity and sonority that makes it far more than the simple occasional bursts of music traditional to radio plays. Indeed, the music to Sword of Orion is testament to the influence of film aesthetics on other media. Film remains something of a gold standard. One also might add that the music is also a testament to the influence of ‘pure’ music aesthetics in film and beyond – something that is not noted as often as it should be. Indeed, many discussions of film music seem to finish abruptly at pointing to ‘what the score does for the narrative’, what it signifies at certain moments. Music has an effect way beyond this, reorganizing the soundtrack as a sensual continuum of an object rather than a succession of pieces of discreet information.

Nicholas Briggs was one of the fans of Doctor Who who became prominent in the culture that filled the absent space of the television serial. As well as writing plays and stories, he also occasionally even appeared as the Doctor in audio plays. With the return of Doctor Who as a high-production values special effects-laden television programme in 2005, Briggs secured himself an important permanent role: as the treated voices for perennial monsters favourites such as daleks and cybermen. In the music CD liner notes, Briggs suggests that he is not a ‘musician’ as some might define it. “As for my abilities of otherwise as a ‘musician’ … without any appropriate [musical] education, I just listen to a scene and hear noises in my head, then try my best to make those noises happen. Somewhere along the line, something a bit like music materialises.” Such an exploratory and improvisatory approach is likely more common in the production of film incidental music than many imagine. Especially seeing as digital technology has ‘democratized’ music making, allowing for sound manipulation and composition without following the traditional path of training, writing and performing music. These days, Garageband ships on each Apple Mac computer, and softstudios such as Ableton Live, Cubase, FL Studio and Logic are relatively cheap and easy to use. Even simply buying Computer Music magazine over the counter in any newsagent furnishes you with a DVD of software that allows instant digital music creation and recording. The ambitious should take note. For Sword of Orion, Briggs used an (expensive) Kurzweil K2000, which he refers to in the sleeve notes as a ‘keyboard’, in seemingly pointed non-technical language. We should remember that in the 1970s, synthesizer players were still referred to as ‘operators’ in the English speaking world rather than as instrumentalists; also Brian Eno strategically called himself a ‘non-musician‘ in order to emphasize his conceptual engagement with music and lack of following the prescribed paths set by musical training and traditions. There has been surprisingly little serious discussion of the difference and relationship between having a musical training (with the prized ‘classical training’ still unproblematically vaunted in the majority of musical circles) and possessing a ‘musical’ sensibility that does not derive from such a route. Film makers can often exhibit strong musical sensibilities in the way they deal with the sonic aspects of their films, such as David Lynch, who acts as his own sound designer and marshals the elements of his films’ soundtracks in a arguably musical manner. Briggs certainly evinces such a sensibility and a strong understanding of drama and dynamics, which allows for a well-integrated score that is in no way a late ‘add-on’ to the drama as is the case in most audio plays, television programmes or films. Indeed, the music ‘works’ on its own as well as with the drama – it has its own musical logic and integrity as well as clearly being carefully constructed as part of the audio drama.

One of the principal characteristics of Briggs’s score is the use of electronic echo effects. Seeing as its appearance one way or another on popular music recordings is endemic, it is surprising that there has only been one notable consideration of echo effects: Peter Doyle’s excellent Echo and Reverb: Fabricating Space in Popular Music Recording. In audiovisual drama, most specifically in film, the use of electronic echo has specific implications: not just denoting large spaces but also psychological spaces, of madness, interior subjectivity or the supernatural. Echo and reverb have also become traditional for the depiction of outer space, as well as inner space. As the Alien (1979) tagline had it, ‘In Space No One Can Hear You Scream.’ Space’s vacuum does not conduct sound, so the association of echo and reverb with outer space is down to the feeling of large open spaces provided by such electronic effects. Echo finds its principal use in space films in music, but also in a genre of music that exploited developing synthesizer technology. ‘Space music’ such as Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze, Hawkwind and more recently Steve Roach and Robert Rich, exploited artificial echo as an essential musical aspect of their soundscapes. Echo-laden music is slightly scary, rendering a sublime of massive sonic space (‘the void’), with the mental interior rendered as a vast exterior, with seemingly no end. Perhaps inside your head you can hear yourself scream (again and again and again).

References

Doctor Who: Sword of Orion (Big Finish no.17, 2001).

Music from Doctor Who: The Eighth Doctor Audio Adventures (Big Finish, 2002).

Peter Doyle, Echo and Reverb: Fabricating Space in Popular Music Recording, 1900-1960 (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2005).

COMMENTS