The Impact of Star Wars

Peter Kramer looks at the story of loss and resurrection that transformed cinema in the late 1970s.

Within a few weeks of its release in May 1977, Star Wars was already being discussed as the beginning of a new era in film history. According to a Chicago Sun-Times headline in June 1977, for example, Star Wars was ‘The First Movie of the 1980s’, leaving behind the negativity and complications of many 70s films.[1] There was disagreement about how this shift was to be evaluated. For the New York Post, in October 1978, Star Wars was a typical youth film, which contributed to a further widening of the ‘gap between generations’ in the cinema audience. The paper wrote: ‘Special effects are in, perception, truth, honest emotion, socially responsible drama are out.’[2]

By contrast, in February 1978 the New York Times saw Star Wars as the most prominent example of a new cycle of ‘general and family films’, which brought diverse social groups together in cinemas and encouraged exhibitors and producers to move away from previously prominent, socially divisive material, notably sex and violence.[3] More specifically, a psychologist interviewed by the New York Sunday News in October 1977 described Star Wars as ‘an example of entertainment with a high absorption value for children’, which was of particular importance for those younger than 12.[4]

Taking my cue from the above responses to Star Wars, in this article I want to demonstrate that, as far as its most popular films are concerned, American cinema was indeed transformed in the late 1970s, and that Star Wars played a crucial role in this transformation. It did so by making an unprecedented immediate impact at the box office, by prolonging that initial impact for thirty-six years (and still counting) through a wide range of products directly based on its story and imagery, and by providing a compelling model of successful cinematic entertainment to both filmmakers and cinema audiences, many of whom were seeking to replicate the initial Star Wars experience.

Indeed, building on the extraordinary impact of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which I have discussed in my most recent article for Pure Movies,[5] Star Wars projected a new vision of what the cinemagoing experience can be like. This vision, which combines the grand audiovisual spectacle and big themes of Science Fiction with the emotional intimacy of family drama, has informed many of Hollywood’s biggest hits since 1977.[6] I discuss these hits in the final section of this article.

I want to start, however, by taking another look at Star Wars, trying to go beyond the familiarity most of us feel with this film so as to rediscover its essential strangeness. I then show how very unusual Star Wars was when compared to box office trends of the preceding decade in the United States, and how strong the immediate response of American audiences to this strange film was.

A Strange Movie

Let’s start with the film’s beginning. Conventionally enough, Star Wars opens with the company logos and fanfares for 20th Century Fox and Lucasfilm, but then, without any further credits for the film’s makers, come silence, stillness and simplicity: ‘A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…’ in blue letters on a black screen. The absence of personal credits suggests that this tale has no particular teller, but is one that has been relayed, like the fairy-tales whose traditional opening line it echoes, from generation to generation.

Yet the word ‘galaxy’ also gives the line a very contemporary, even futuristic feel, which is confirmed by the title ‘Star Wars’ that next explodes onto the screen, together with another orchestral fanfare. The title exceeds the frame’s boundaries, but then quickly becomes smaller, disappearing into the background which, it can now be seen, is made up of the night sky, or perhaps it is deep space, dotted with countless tiny stars.

Movement into the depth of the screen, which draws us in, also characterises the next set of words appearing at the bottom of the frame: ‘It is a period of civil war.’[7] The subsequent text, slowly receding into space, provides the backstory and a broader, political context for the action to follow, as one might expect from the similar looking introductory roll-ups of movie serials of the 1930s and 1940s, or from the voiceovers frequently used to introduce historical epics.

According to the film’s introduction, an ‘evil Galactic Empire’ (empires being a traditional subject for epics) is fought by ‘Rebel spies’, who have stolen the plans to the empire’s ‘ultimate weapon… an armored space station with enough power to destroy an entire planet’. The stakes are very high indeed, then, with the lives of billions of people who might inhabit such a planet in the balance. At the centre of the present action is, perhaps somewhat surprisingly, a woman – ‘Princess Leia,… custodian of the stolen plans that can save her people and restore freedom to the galaxy…’

There is much that sounds familiar – from fairytales, movie serials, historical epics, Science Fiction etc. – and predictable in the story outline given at the film’s beginning. Yet, the ensuing narrative is full of curious and surprising elements. Here are some of them:

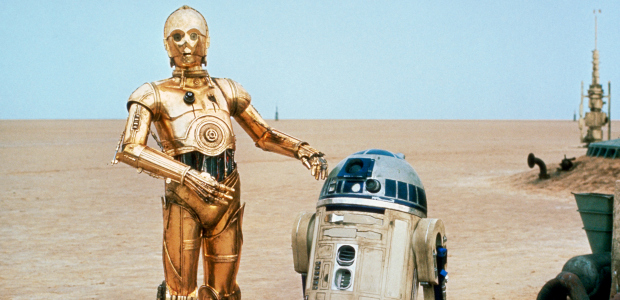

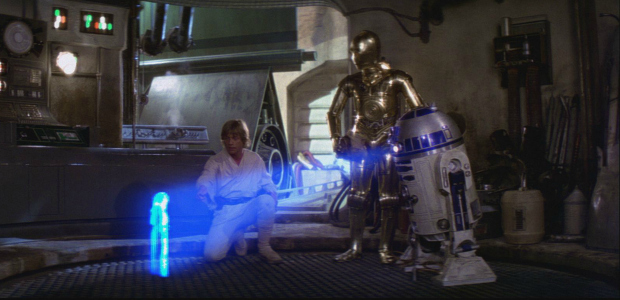

– the early capture of the film’s apparent protagonist, Princess Leia, and the subsequent prolonged focus on two robots, one humanoid, the other looking like a wandering trashcan;

– the long delayed and somewhat accidental entrance of the film’s true hero, Luke Skywalker;

– the multiple losses of parental figures Luke has to endure (his aunt and uncle, and his mentor Obi-Wan Kenobi, in addition to the parents he lost before);

– the somewhat casual destruction of a whole planet to demonstrate the Death Star’s might, and at the same time the privileging of spiritual over technological power on both sides of the conflict (with Luke and Obi-Wan as well as their main opponent Darth Vader all drawing on ‘the Force’);

– the complex and shifting historical and generic associations of characters, props, situations and locations (a princess fighting stormtroopers on a spaceship, duels with swords that are also lasers, the disempowerment of the ‘Imperial Senate’, saloon brawls with aliens in a space port etc.);

– and, at the end, an unresolved love triangle (between Luke, Leia and Han Solo) and a villain that has managed to escape.

Many of these curious aspects of Star Wars make sense in retrospect, especially as we now know the film’s sequels and prequels, but in 1977 people had to take Star Wars on its own terms. At that time, the film’s status as a curiosity was enhanced by the fact that it did not look or feel anything like Hollywood’s big hits of the preceding decade (with the exception, perhaps, of certain aspects of 2001: A Space Odyssey) and did not feature many attractions that American audiences would have been familiar with from their recent visits to the cinema.

Today, when Star Wars in all its incarnations is a highly familiar presence in American (and indeed in world) culture, and any new product related to the saga can rely on all the interest, experiences and expectations generated by countless earlier Star Wars products, it is difficult to remember that there was nothing ‘pre-sold’ about the first film in 1977.

Star Wars had no major stars, and among the actors only Alec Guinness was well known, but hardly a box office draw. The film’s writer-director George Lucas had previously made only two films, the first of which (THX 1138, 1971) had been a Science Fiction film and a flop, while the second (American Graffiti, 1973) had been a huge hit but, as a pop music driven comedy-drama about early 60s small town youth in Modesto, California, it hardly was a precedent for Star Wars, and in any case Lucas was not widely known by name.

Perhaps most importantly, unlike the vast majority of previous superhits in Hollywood history, Star Wars was not a direct adaptation of material that had already been successful in another medium. From the beginnings of Hollywood in the 1910s, in every decade the very biggest hits at the US box office – The Birth of a Nation (1915), The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and Ben-Hur (1925), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Gone With the Wind (1939), The Best Years of Our Lives and Duel in the Sun (both 1946), The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ben-Hur (1959), The Sound of Music and Doctor Zhivago (both 1965), The Exorcist (1973) and Jaws (1975) – had, with very few exceptions, been based on best-selling novels, long-running Broadway shows, fairy-tales, the Bible or, failing all this, on the lives of famous historical figures or on well known historical events.[8]

Star Wars by contrast belonged to the very small group of Hollywood superhits which managed to assemble a new audience, rather than drawing on the built-in audiences of their source novels or stage versions, their featured songs and/or their stars, or on the already established appeal of familiar historical figures and events.

Judging by the responses of reviewers (to be discussed below), one reason for the film’s ability to attract so many people was that, while it was not based on any particular well-known fictional story or historical episode, it resonated more generally with a wide range of familiar character types and storytelling traditions. The film’s title, its tagline (‘A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away’) and its posters – featuring space ships, light sabers, robes, gun play, robots and a potential love triangle – sent mixed signals about the generic traditions the film drew on: Science Fiction, combat movie, medieval legend, historical romance, fairy-tale, ancient myth, epic, Western, adventure.[9]

Yet, once again we have to note that with the exception of the wide-ranging adventure category, none of these traditions had met with much box office success in the years before Star Wars.[10] For example, since 1972 there had been only one Western (the parodic Blazing Saddles, 1974) and one war film (Midway, 1976) in the annual lists of the ten top grossing movies in the US, no film with truly epic dimensions apart from Midway, no Science Fiction and no film one could characterize as a historical romance, medieval legend or ancient myth.[11] While since 1972 there had been a range of children’s films such as Herbie Rides Again (1975) in the annual top ten, with more or less pronounced fairy-tale elements, their individual box office returns were limited, amounting to only a fraction of the revenues generated by the biggest hits.

Thus, rather than building on recent box office trends, Star Wars departed from them, reviving older traditions in cinematic, as well as non-cinematic, entertainment, which helps to explain why so many people welcomed it so enthusiastically as both strikingly new and utterly familiar.

Initial Responses

The film industry’s leading trade paper Variety wrote: ‘Like a breath of fresh air, Star Wars sweeps away the cynicism that has in recent years obscured the concepts of valor, dedication and honor.’[12] The paper valued Star Wars as a return to, and celebration of, traditional Hollywood entertainment, comparing it to the ‘genius of Walt Disney’ and calling it ‘a superior example of what only the screen can achieve, and closer to home, it is another affirmation of what only Hollywood can put on a screen.’

According to the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, Star Wars was an ‘irresistible fantasy seductive enough to make lifetime movie addicts out of the young and born-again innocents out of the rest of us’; it ‘gives us back our dreams … [and] makes us feel as if we’re watching our very first movie.’[13] Just as, in this account, Hollywood cinema was re-born with Star Wars, its viewers were born again as true believers in the power of cinema, with thirty-three year old writer-director George Lucas as their emotional and spiritual guide. Here is the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner again: ‘“I believe, I believe” may be the only proper response to Star Wars…. George Lucas is Peter Pan and we’re wide-eyed children he sweeps off into Never-Never Land.’[14]

Thus, the film combined forward-looking Science Fiction with a return to deeply rooted cultural traditions of the movies, of children’s entertainment, of popular history and legend: ‘Star Wars is as much about the past, our shared past, as it is about the future. Young Luke Skywalker might be Prince Valiant, a Musketeer, Captain Blood, John Wayne, Errol Flynn, the Lone Ranger, Alice in Wonderland or Dorothy in the Land of Oz.’[15]

As far as many of its first reviewers were concerned, then, Star Wars managed to reinvent mainstream cinema – by re-injecting a sense of wonder into the cinema-going experience, by thus offering a vision to audiences of what this experience could be, and by raising the possibility that it might have the power to affect people’s lives both inside and outside the movie theatre.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence that children as well as adults were indeed deeply affected, even transformed, by their viewing – or, more likely, multiple viewings – of Star Wars. Tom Stempel’s oral history of cinema-going in the U.S. dedicates a whole chapter to the film, quoting several statements such as the following by a man who was seven when he first saw Star Wars in the late 1970s: ‘[F]rom that point on, I was changed forever. Here was a silly science fiction film that took itself seriously, and I believed in it. … That movie drove me crazy; I was actually addicted to it.’[16]

Amongst the children getting hooked on the film were many future writers and directors, including Kevin Smith, who has indulged his Star Wars obsession in most of his movies from Clerks (1994) onwards. He wrote: ‘I was married to Star Wars when I was a kid. I had all the toys, wallpapered my bedroom with the posters and images cut out of magazines, action figure card-backs, and Burger King giveaways. … And whether I wanted it to or not, Star Wars influenced – and sometimes defined – important epochs in my life, teaching me how to conduct myself in a galaxy not very far away at all.’[17]

In 1977, the film also made a strong impact on James Cameron, then a twenty-two year old amateur filmmaker who, after having initially been inspired by 2001 to try to become a filmmaker, was given the final push to go professional by Star Wars. He later said: ‘That was the movie that I wanted to make. After seeing that movie I got very determined.’[18] What impressed Cameron most were the film’s groundbreaking special effects, which increased the power of filmmakers to translate their imagination into film: ‘I saw that all the things I had been seeing in my head all along could now be done.’[19]

All this enthusiasm for the film translated into unprecedented box office returns and critical as well as popular acclaim. Star Wars was given a narrow, yet high profile release, being initially shown in fewer than 50 cinemas which were equipped with 70mm projectors and the new Dolby stereo sound system, and mostly charged higher than usual admission prices in response to huge demand; from its fourth week onwards the film slowly went into wider release playing in 1,000 cinemas by week 11 (in early August).[20]

During the same period, toy manufacturers and other companies rushed to make merchandising deals which, it was correctly predicted, would lead to ‘possibly the largest ever’ ‘product bonanza’ in Hollywood history.[21] At the end of 1977, the film was still being shown in numerous cinemas and complaints about a shortage of Star Wars merchandise for the Christmas season were widespread. Its U.S. rentals (that is the distributor’s share of the money paid at the box office, usually about 50%) were a record $127 million, more than twice as much as the year’s next biggest hit, and over $5 million more than Jaws (1975), the previous all-time record holder, had amassed by then.[22]

What is more, Star Wars was already celebrated as one of the all-time greats. In a 1977 survey conducted by the American Film Institute among its 35,000 members the film was voted one of the ten best American movies ever, and a readers’ poll conducted in the same year by the Los Angeles Times came to the same conclusion.[23] The following spring, Star Wars won Academy Awards for Best Art Direction, Sound, Original Score, Editing, Costume Design, Visual Effects and a Special Achievement Award for sound effects, as well as being nominated for Best Picture, Original Screenplay and Supporting Actor (Alec Guinness). Later that year, in a critics’ poll organised by the film magazine Take One both Vincent Canby of the New York Times and Richard Schickel of Time declared Star Wars to be one of the ten best films of the preceding decade, while college students voted it their second favourite film of all time (after Gone With the Wind, 1939).[24]

Amazingly, Star Wars continued to attract audiences in 1978 and, after a brief withdrawal from theatres, was successfully re-released in the summer of 1978.[25] In October 1978, Star Wars figures and vehicles were still the top selling toys in the country.[26] By the end of the year its rentals had grown to $165 million, which meant that, even when ticket price inflation was taken into account, Star Wars was now ahead of all other films, except for Gone With the Wind, which had the advantage of having been re-released numerous times over the decades.[27]

We could go on with the story of the subsequent re-releases of Star Wars (most notably in 1997), of the theatrical releases of its sequels and prequels, of the saga’s appearance on video and DVD, of the continued production of countless toys, games, books and other products based on Star Wars. But instead I now want to examine the initial film’s impact on the kinds of film that have succeeded at the American box office since 1977.

Long-Term Resonance

The enormous influence Star Wars exerted on American filmmakers and audiences becomes obvious when we look at Box Office Mojo’s inflation-adjusted all-time chart.[28] As of January 2014, Star Wars is ranked second (after Gone With the Wind), and the top one hundred positions on this chart feature fifty-one films released after Star Wars. Many of these were in one way or another influenced by Star Wars. Most importantly, there are two sequels and three prequels. Then there are three Indiana Jones films in Box Office Mojo’s top 100; these are in effect Star Wars spin-offs with a modified Han Solo figure transposed into the world of 1930s political intrigue (with strong religious and mythical overtones).

Independence Day (1996) is a straightforward rip-off of key images and scenes from Star Wars (e.g. the enemy space ship entering the frame from above at the beginning, and the climactic entry into, and destruction of, the moon-sized enemy base at the end). Men in Black (1997) can be seen as an extension of the cantina scene in Star Wars. Toy Story 3 (2010) is the latest instalment in a series of films which have consistently engaged with the Star Wars saga (most notably, Toy Story 2 [1999], which is placed just outside the top 100, replays the climactic encounter between Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader and the revelation that Vader is Luke’s father, thus reminding us that as a space action toy Buzz Lightyear had originally been situated in a Star Wars-like universe).

The world of the children in E.T. (1982) is full of Star Wars toys (featured in the scene in Elliott’s bedroom in which he begins to explain his world to the extraterrestrial) and references to Star Wars characters (Elliott and his brother mimic Yoda’s voice, and on Halloween E.T. encounters a child in a Yoda costume on the street). Since the Lord of the Rings novels were among the many inspirations for the Star Wars saga, it is not surprising to find numerous parallels (e.g. Gandalf and Obi Wan, the Ring and the Dark Side of the Force); all three Lord of the Rings films are in Box Office Mojo’s top 100. Last but not least Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001) tells another story of an orphaned boy, who like Luke Skywalker lives unhappily with his aunt and uncle until he is told that he is a wizard and goes off to receive training in wizardry which has its dangers because some wizards go over to the dark side, amongst them the very person who killed his parents.

More generally, we can note the prominence of two important generic elements of Star Wars in the superhits of subsequent decades: Science Fiction and supernatural fantasy (especially the foregrounding of spiritual forces). Both of these generic elements were largely absent from Hollywood’s superhits before 1977, yet, in addition to the films already mentioned, one or both of these elements can be found in the following post-1977 films in Box Office Mojo’s top 100: Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Superman (1978), Ghostbusters (1984), Back to the Future (1985), Ghost (1990), Aladdin (1992), Jurassic Park (1993), The Lost World (1997), The Sixth Sense (1999), Shrek 2 (2004), Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009), Avatar (2009) and Marvel’s The Avengers (2012) as well as several Batman, Spider-Man, Pirates of the Caribbean and Hunger Games films. Even The Lion King (1994) features the spiritual presence of Simba’s father, and The Passion of the Christ (2004), of course, foregrounds the presence in this world of divine and satanic forces.

Furthermore, the superhits from 1977 onwards include more orphaned boys like Luke (it should be noted that while we find out in the sequels that Luke’s father is alive, in Star Wars he is presented as an orphan). These orphans include the young Superman, Aladdin, Harry Potter and Spider-Man. Batman (1989) also emphasizes the hero’s traumatic loss of his parents when he was a child, while Home Alone (1990) is about a boy who wishes his family would just leave him alone, which, by accident, they do, so that he is indeed temporarily orphaned.

There are also several films where the protagonist’s mother is alive, but the father’s death, or absence, is emphasised. These include E.T., The Lion King and The Sixth Sense. In Forrest Gump (1994) the father is not dead, but he might as well be – he has gone never to return -, and the mother of the childlike hero dies in the course of the film. Even Twister (1996) starts with a scene in which a child witnesses the father’s death; only here it is a girl. Similarly, The Hunger Games (2012) revolves around a girl who has lost her father and, in his stead, has to take care of her mother and her younger sister. And in Titanic (1997) it is made clear that the heroine’s unstable social position, which has forced her into an engagement with a man she does not love, is a result of her father’s death and his irresponsibility while he was still alive.

In addition, there is the horrific opening of Finding Nemo (2003), in which most members of a large family are slaughtered; the surviving father then spends the rest of the film trying to protect his only surviving son. Similarly, in Mrs. Doubtfire (1993) a divorced father tries to be near to, and take care of, his children, while in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and in Jurassic Park (1993) – and also in Monsters Inc. (2001) – adult males reluctantly take on a paternal role with regards to the children they encounter, whereas both Indiana Jones and the Lost Crusade (1989) and The Lost World (1997) focus on the relationship between fathers and their biological children. That relationship is also central to Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Back to the Future.

Looking at these patterns among the post-1977 films in Box Office Mojo’s top 100, we can indeed say that Star Wars established a template for subsequent superhits, mainly through combining Science Fiction spectacle with a focus on spirituality and intimate family drama (concerning in particular the relationship between parents and children, and most especially between fathers and sons). What is more, Star Wars showed that this combination could work for all-inclusive family audiences, bringing together the cinema’s core audience of teenagers and young adults with children and their parents. Consequently, most of Hollywood’s superhits since 1977 are similarly suitable for all age groups, which was not the case for many of the superhits from 1967-76 such as The Graduate (1967), The Godfather (1972), The Exorcist (1973) and Jaws (1975). Furthermore, the use of children or childlike characters as protagonists and the fantastic settings and action of the films make Star Wars and the majority of later superhits particularly accessible for children. At the same time, they offer adults (as well as youth) a nostalgic return to the pleasures of the entertainments of their childhood (fairy-tales, toys, children’s TV programmes, movie serials, comic strips, ghost stories, amusement park rides etc.). Finally, Star Wars and most of the later superhits were released in the run up to, or during the summer or Christmas holidays, so as to make it easier for family groups to attend. Because they offer an adventure for the whole family, and because their stories revolve around familial or quasi-familial relationships, we can call most of the superhits since 1977 family-adventure movies.[29]

Let’s summarise the basic features of this type of film:

– the privileging of familial love and friendship over romantic love;

– a focus on intergenerational relations, mostly within biological or substitute families and in most cases with a focus on a young male protagonist;

– an emphasis on dead, absent, irresponsible, weak or evil fathers or otherwise dysfunctional familial relations;

– a move towards the maturation and/or redemption of the protagonist, the regaining of familial closeness, and the integration of families into wider social networks;

– the shift from fairly realistic everyday sequences towards the beginning of the film, often emphasising the protagonist’s fears and wishes, into more or less fantastic adventure and spectacle, which realise those fears and wishes;

– in many instances explicit reflections on the nature of storytelling which suggest a parallel between the adventure the protagonist embarks upon and the audience’s experience of the film, between the social networks the protagonist is (re-)integrated into by the end of the film and the shared experience of the people in the auditorium.

Conclusion

The original Star Wars trilogy tells a story of loss and cinematic resurrection. Teenage orphan (or so it initially seems) Luke Skywalker embarks on his big adventure after a short movie is shown to him (Leia’s call for help), and after the original loss of his parents is replayed through, and compounded by, the death of his aunt and uncle, who had taken care of him but who had also been holding him back on their farm. In the course of his adventure, his two mentors (Obi Wan and Yoda) die as well, but he also makes many new friends. By gaining access to the mysterious power of “the Force” Luke is then able not only to defeat the Evil Emperor, who is ultimately responsible for all his losses, but also to redeem his own father who had gone over to the Dark Side. At the very end of the trilogy, during victory celebrations, Anakin Skywalker as well as Obi Wan and Yoda appear to Luke – and only to him – as spirits. In fact, they appear as superimposed images on the screen, that is, as projections within the film which is being projected on the screen. Thus it is the power of cinema that, in response to Luke’s experience of loss, brings loved ones back to life.[30]

Due to the enormous success of Star Wars and its first two sequels, American filmmakers and audiences repeatedly turned to similar stories after 1977, so that many of Hollywood’s superhits since then fit the Star Wars template: Loved ones (family members or lovers) have been, or are being lost, and this loss influences the protagonists’ outlook on the world; their wishes and anxieties gradually – or occasionally very abruptly – take shape in their reality, often magically so; they achieve an emotional resolution in the end, sometimes a spiritual reunion with those they have lost, yet rarely a reunion in the here and now; however, an alternative, closely knit social network has been established, typically going beyond the sphere of family and romance.

And always the power of cinema itself to bring fantastic scenes to life, to translate an individual’s wishes and anxieties, dreams and nightmares into a shared reality, to make up – albeit only temporarily and imaginarily – for all our losses, to provide us with a stronger sense of communal bonds, is being foregrounded and celebrated. Hollywood’s biggest hits of recent decades thus present a very optimistic vision of the impact of cinema on, and the role cinema can play in, our lives.

[1]Roger Simon, ‘Star Wars: The First Movie of the 1980s’, Chicago Sun-Times, 5 June 1977.

[2]Hollis Alpert, ‘Movies in the Age of Youth’, New York Post, 15 October 1978.

[3]Judy Klemesrud, ‘Family Movies Making a Comeback’, New York Times, 17 February 1978, p. C10.

[4]Joe Gallick, ‘Choosing a Healthy Show for Children’, New York Sunday News, 9 October 1977, p. L10.

[5] Peter Krämer, “2001: A Space Odyssey: The Ultimate Spectacle”, Pure Movies, 19 January 2014, https://www.puremovies.co.uk/columns/2001-a-space-odyssey-the-ultimate-spectacle/.

[6] I have recently explored how this vision is realised by Contact and Gravity in articles published in Pure Movies and on the ThinkingFilmCollective blog: Peter Krämer, “Making Contact”, Pure Movies, 20 November 2013, https://www.puremovies.co.uk/columns/making-contact/; Peter Krämer and Rupert Read, “Gravity‘s Pull”, ThinkingFilmCollective blogspot, 22 January 2014, http://thinkingfilmcollective.blogspot.co.uk/2014/01/gravitys-pull.html.

[7] The original release version of Star Wars did not include the heading ‘Episode IV: A New Hope’.

[8]For the early decades of the 20th century, see the chart in Joel W. Finler, The Hollywood Story, London: Wallflower, 2003, pp. 356-7. For the period since 1937, see Box Office Mojo’s all-time box office chart which adjusts revenues for ticket price inflation: http://boxofficemojo.com/alltime/adjusted.htm.

[9] Cp. Olen J. Earnest, ‘Star Wars: A Case Study of Motion Picture Marketing’, Current Research in Film, 1, 1985, pp. 1-18.

[10]Cp. the annual US box office charts for the years 1967-76 in Peter Krämer, The New Hollywood: From Bonnie and Clyde to Star Wars, London: Wallflower Press, 2005, pp. 106-9. Adventure films such as Deliverance (1972) and The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams (1975) formed a strong box office trend among both adult and family-oriented films. Furthermore, some of the large-scale destruction in Star Wars can be related to disaster movies such as Earthquake (1974), and its spiritual themes to demonic possession films such as The Exorcist (1973). Both types of film also emphasise, like Star Wars, various forms of special effects.

[11]‘Epic’ is here understood as a film that sets its often intimate main story against the backdrop of important events and developments in human history, which are staged in a spectacular fashion. This definition excludes films such as The Godfather.

[12]A. D. Murphy, review of Star Wars, Variety, 25 May 1977, reprinted in Chris Salewicz, George Lucas: The Making of His Movies, London: Orion, 1998, p. 124.

[13]Richard Cuskelly, ‘Star Wars: “I Believe, I Believe”’, Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, 25 May 1977, p. B1. For a discussion of closely related press responses to the film, see Peter Krämer, ‘“It’s aimed at kids – the kid in everybody”: George Lucas, Star Wars and Children’s Entertainment’, in Yvonne Tasker (ed.) Action and Adventure Cinema, London: Routledge, 2004, pp. 365-6.

[14]Cuskelly, ‘Star Wars: “I Believe, I Believe”’, p. B1.

[15]Ibid., p. B4.

[16]Tom Stempel, American Audiences on Movies and Moviegoing, Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2001, p. 117. For a systematic study of Star Wars fans, see Will Brooker, Using the Force: Creativity, Community and ‘Star Wars’ Fans, New York: Continuum, 2002.

[17]Kevin Smith, ‘Married to the Force’, in Glenn Kenny (ed.), A Galaxy Not So Far Away: Writers and Artists on Twenty-Five Years of ‘Star Wars’, New York: Henry Holt, 2002, pp. 72-3 (emphasis in the original).

[18]Christopher Heard, Dreaming Aloud: The Life and Films of James Cameron, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1997, pp. 9-10.

[19]Marc Shapiro, James Cameron: An Unauthorized Biography of the Filmmaker, Los Angeles: Renaissance Books, 2000, p. 55.

[20]Olen J. Earnest, ‘Star Wars: A Case Study of Motion Picture Marketing’, pp. 14-5; Roger Cels, ‘Ticket Price Hikes a Factor in Pace of Star Wars’, Hollywood Reporter, 2 June 1977, pp. 1, 4; Sheldon Hall, ‘Blockbusters in the 1970s’, in Linda Ruth Williams and Michael Hammond (eds), Contemporary American Cinema, Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2006, p. 170. According to Hall, Star Wars opened mid-week in 32 cinemas, but was shown in 43 cinemas during its first weekend.

[21]Frank Barrow, ‘Star Wars Product Bonanza’, Hollywood Reporter, 8 June 1977, pp. 1, 9.

[22]‘All-Time Film Rental Champs’, Variety, 4 January 1978, p. 25. When referring to US or domestic revenues, Variety in fact includes Canada. By the same token, when referring to non-US or foreign markets, Canada is excluded.

[23]Cobbett Steinberg, Film Facts, New York: Facts on File, 1980, pp. 142-4, 189.

[24]Ibid., pp. 156-68, 182-3. For further evidence of the film’s positive reception by critics and by the industry itself see Krämer, The New Hollywood, pp. 95-6.

[25]Earnest, ‘Star Wars: A Case Study of Motion Picture Marketing’, p. 17.

[26]‘Toy Hit Parade’, unidentified 1978 trade paper clipping reproduced on ‘Mego Museum Trade Ad and Press Archive’, http://www.megomuseum.com/megolibrary/adarchive/1978/topten.html, accessed 2 August 2006.

[27]Steinberg, Film Facts, pp. 3-4.

[28] See http://boxofficemojo.com/alltime/adjusted.htm, last accessed 23 January 2014.

[29] Cp. Peter Krämer, ‘Would You Take Your Child To See This Film? The Cultural and Social Work of the Family-Adventure Movie, in Steve Neale and Murray Smith (eds), Contemporary Hollywood Cinema, London: Routledge, 1998, pp. 294-311.

[30]The prequel trilogy tells a much more pessimistic version of this story, whereby Annakin Skywalker’s separation from his mother and his emotional attachment to the young woman who then takes care of him lead to his transformation into Darth Vader. The death of Annakin’s mother makes him murderous, and his forbidden love for Padme makes him vulnerable to the manipulations of Darth Sidious who foresees Padme’s death and promises to give Annakin the power to prevent it, which leads to actions through which Annakin inadvertently brings about Padme’s death in childbirth.

COMMENTS