‘The Graduate’ at 50

On its anniversary, Peter Kramer takes a closer look at the film’s critical and commercial success, and at the rather puzzling way in which it tells Benjamin’s story.

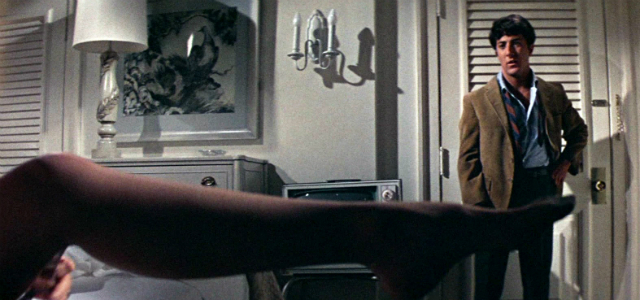

A young man returning home to his parents in Los Angeles after graduating from college is seduced by the wife of his father’s business partner and then falls in love with her daughter. This unusual love triangle, presented, with a lot of humour, in both erotically charged and touchingly emotional scenes, is at the centre of The Graduate, which was released fifty years ago in December 1967.

There is much else going on in the film. Despite all his great achievements at university – winner of a prestigious scholarship, head of the debating team, track star – and the obvious wealth of his family, the film’s ‘hero’, Benjamin Braddock, has ill-defined and paralysing anxieties about the future and is at odds with the views of his parents and their friends, especially when he is told that the future is ‘Plastics!’. The story of The Graduate, then, is about how Benjamin attempts to overcome his paralysis, first through sex and later through love. This is done with plenty of verbal, situational and visual comedy, a playful handling of cinematic conventions (especially where editing is concerned) and the lyricism of Simon & Garfunkel songs on the soundtrack, most famously ‘Mrs. Robinson’, which is a tribute to the older seductress in the movie.

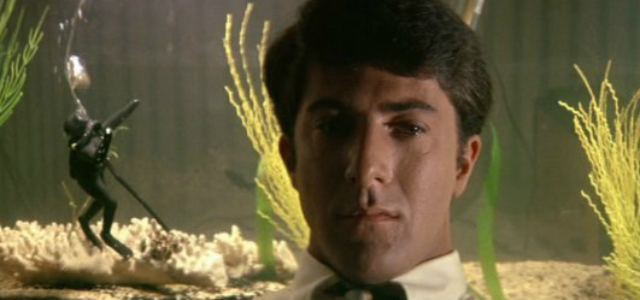

Mrs. Robinson was played by Anne Bancroft, the only established star in the movie, who also received top billing. In the role of Benjamin, the film introduced Dustin Hoffman to the world and immediately established him as one of the defining movie stars of the era. Katherine Ross, playing Mrs. Robinson’s daughter Elaine, was another newcomer, who went on to feature in more classic films of the late 1960s and the 1970s, notably Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

Upon the initial American release of The Graduate in December 1967, reviewers were not always sure what to make of it: Were audiences really meant to sympathise with Benjamin and his ‘revolt’, and did the film offer a valid critique of contemporary society? Yet, there was general agreement early on that The Graduate was an important film, a milestone even.

When, on 8 December 1967, Time magazine’s cover announced ‘The New Cinema: Violence…Sex…Art’, with the cover story inside declaring that there was a ‘renaissance’ in Hollywood cinema, which was connected to upheavals in American culture, society and politics often to do with generational conflict, the forthcoming release of The Graduate, described as ‘an alternately comic and graphic close-up’ of a young man ‘whose central fantasies come terrifyingly true’, was offered as evidence.

This was confirmed when, to everyone’s surprise, The Graduate became one of the biggest box office hits in the United States, not only of the late 1960s but of all time. In the months and years after its initial release, the film also accumulated critical accolades, soon being regarded as one of the great masterpieces of American cinema. In this essay, I take a closer look at the film’s critical and commercial success, and at the rather puzzling way in which it tells Benjamin’s story.

Extraordinary Impact

Few movies have made as big an impact in the United States as The Graduate did upon its release in December 1967. To begin with, despite considerable disagreement among the earliest reviewers, the film received huge critical acclaim. The Graduate was declared to be one of the ten best films of the year by both the New York Times and the National Board of Review. The Hollywood Foreign Press Association awarded it the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture in the ‘Musical/Comedy’ category, and gave the award for Best Actress in this category to Anne Bancroft, while also identifying its two unknown young leads, Hoffman and Ross, as the ‘Most Promising Newcomers’ of the year. Similarly, Quigley Publications’ annual survey of film exhibitors revealed that they considered Hoffman and Ross most likely of all newcomers that year to achieve major stardom in the future.

Furthermore, the Writers Guild of America judged The Graduate to be the ‘Best Written American Comedy’ and the Directors Guild declared its director Mike Nichols to be the best of the year, as did the New York Film Critics Association and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Finally, The Graduate was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning for Best Director.

Very soon, The Graduate also came to be regarded as one of the best, or most important, American films of the decade, even of all time. In 1970, it was included in Time magazine’s top ten films of the 1960s, and two surveys carried out by the Los Angeles Times that year found that both the newspaper’s readers and a selection of filmmakers voted The Graduate the best film of the 1960s.

When the University of Southern California asked a panel of American filmmakers and critics in 1972 to name ‘the most significant movies in American cinema history’, The Graduate made it into the top 30, while a 1977 survey of the 35,000 members of the American Film Institute (AFI) concerning the greatest American films of all time placed The Graduate in the top 50. In another Los Angeles Times survey from 1977 about readers’ favourite movies of all time, The Graduate came in at number 14. Finally, when the AFI in 1998 polled ‘more than 1,500 leaders from across the film community’ to determine ‘the 100 greatest American movies’ The Graduate was ranked seventh.

In addition to all this acclaim from critics, members of the film industry and the general public, The Graduate was more than just another big hit at the US box office; its success was in fact unprecedented for the kind of movie it was. Rather than being adapted from well known source material by well established Hollywood personnel, The Graduate was based on an obscure 1963 novel by Charles Webb; it was only the second movie of its director Mike Nichols, who, as already mentioned, gave the film’s only star (Anne Bancroft) a supporting role while casting two unknowns in the lead roles.

Unlike most of the really big hit movies of the second half of the 1960s – ranging from The Sound of Music (1965) and Dr. Zhivago (1965) to Funny Girl (1968), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – The Graduate was not particularly expensive, nor was it released by a major Hollywood studio. Instead it was financed and distributed by the independent company Embassy Pictures.

And yet, staying in American movie theatres for over a year, The Graduate made more money than almost all other movies, not only in the late 1960s but in all of American film history up to this point. When the trade paper Variety presented its updated list of ‘All-Time Boxoffice Champs’ in the United States in January 1970, The Graduate was in third place, beaten only by The Sound of Music (a film based on one of the longest running shows in Broadway history) and Gone With the Wind (the 1939 adaptation of one of the biggest bestsellers in American publishing history).

Even when box office figures are adjusted for ticket price inflation, only seven films released before 1967 were more successful than The Graduate. At present, Box Office Mojo’s inflation-adjusted list of top grossing movies in the US places The Graduate at number 22, only a few places below Avatar (2009), and above Jurassic World (2015) and Marvel’s The Avengers (2012).

The Graduate earned $105 million at the US box office, mostly in 1968. Given the average ticket price that year of $1.31, we can calculate that it sold an astonishing 80 million tickets, which is equivalent to 40% of the American population at the time. This does not mean that four out of ten Americans saw the film in the cinema, because from contemporary newspaper reports we know that many people watched the film several times. Still, very few films before, or after, The Graduate have ever reached as large a share of the American population in cinemas.

The Youth Audience

From circumstantial evidence it is possible to deduce a lot about the composition of the film’s audience. Surveys in the late 1960s revealed that about three quarters of all cinema tickets in the United States were bought by 12-29 year olds, and that many older people objected very strongly to the kind of transgressive material (to do with nudity and sexual relations) presented in The Graduate, while the film’s marketing, which ‘suggested’ that it was only ‘for mature audiences’, would have made it difficult for young teenagers and pre-teen children to attend. What is more, surveys also found that working-class, rural and uneducated people only rarely went to the cinema at that time.

It would seem, then, that The Graduate owed its enormous success primarily (but by no means exclusively) to middle-class, city youth in their late teens and twenties, especially those attending, or having graduated from, high school and also possibly college. Such youth made up an unusually large proportion of the American population, because the so-called baby boom, caused by high birth rates from the mid-1940s onwards, had swelled the number of Americans who were in their teens and twenties in 1967/68, and most of them received at least a high school education. (In fact, both Benjamin, who turns 21 in the story, which presumably takes place in 1967, and Elaine, who is a little bit younger than Benjamin, were born in the mid-1940s, thus representing the oldest cohorts of the baby boom.)

Therefore the most important signal that the surprise success of The Graduate sent to the Hollywood studios was that it was possible to make huge amounts of money by targeting their output primarily at educated, middle-class youth in cities, rather than making films for everybody. In fact, by increasingly focusing on this narrow target audience during the next few years, Hollywood inadvertently alienated many potential cinemagoers, and attendance levels sank to their lowest point in history in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

However, it is interesting to note that when The Graduate was first shown on American television in August 1973 (probably in a heavily edited version), it achieved a 30.5 rating, which means that almost a third of all television households were tuned in, and almost half of the households that were watching television that evening. Prime-time network television at this time was characterised by family viewing which suggests that, in addition to being a youth phenomenon, The Graduate could also serve as family entertainment, although it had originally been understood as the ultimate youth movie.

Mixed Reviews

An examination of the film’s initial American reviews reveals how people responded to The Graduate during its original release in 1967/68, what they liked or disliked about it, and how they made sense, or failed to make sense, of it.

Variety described The Graduate as a ‘delightful, satirical comedy-drama about a young man’s seduction by an older woman, and the measure of maturity which he attains from the experience’. Yet, while praising the screenplay and the cast, the review also noted that there was something quite unsatisfactory about the film’s final third, during which Benjamin tries to, and eventually does, win back Elaine, who has rejected him after finding out about his affair with her mother.

Where Variety complained that the film’s ‘switched on cinematics’ eventually became tiring, Time magazine judged the film’s ostentatious style, with its ‘tricky sound overlaps’ and ‘quick jump cuts’, to be ‘alarmingly derivative’. The Village Voice similarly noted that while director Mike Nichols had ‘a personal style’, his visual ‘eclecticism’ eventually ‘gets out of hand’. Yet Women’s Wear Daily admiringly likened The Graduate to European ‘art films’.

It wasn’t just the film’s style that was seen to stand out, for better or for worse, from Hollywood’s regular output, but also its content. The New Leader observed: ‘A few taboos are, indeed, broken’, mainly to do with transgressive sexual relationships and nudity. Indeed, the Catholic Film Newsletter pointed out that the film’s focus on adultery and some of its language might be offensive to viewers, yet also assured its readers that Mike Nichols was ‘a savage moralist’, among other things showing ‘how joyless a thing an affair can be’.

Most reviewers agreed that The Graduate was a satire, exaggerating and thus critiquing many aspects of contemporary culture. For Variety the target was ‘a materialistic society’, for the fan magazine Modern Screen it was ‘middle class suburban life’, for the New York Times ‘the piteous immaturity and anti-intellectualism of a large proportion of the supposedly educated and cultivated affluent middle-class’, and for the Catholic Film Newsletter ‘just about anything thought of in connection with the “Establishment”’, such as ‘affluence, the generation gap, conformity, uninvolvement’.

Reviewers disagreed about whether this satire actually worked. The New York Morning Telegraph thought that the story was simply not very believable and its critique therefore toothless, and Women’s Wear Daily described the film as a ‘fantasy’ and went on to declare: ‘While its tone is clearly existentialist, exactly what that voice is saying is not nearly so clear.’ The Catholic Film Newsletter argued that ‘[t]he targets of [the film’s] humour … are a bit broad and ones already rejected by the general population’, which made its satire largely superfluous.

Several reviews agreed with Variety that there was a troubling shift occurring at some point in the second half of the movie. Time wrote that The Graduate ‘begins as a genuine comedy’ and then ‘degenerates into spurious melodrama’. The Catholic Film Newsletter pointed out that ‘Ben’s obsessive pursuit of Elaine and its romantic implications are slightly jarring after all the stones already cast at false ideals’ in the first part of the movie. From a certain point onwards, all Benjamin can think of is to marry Elaine, although from Mrs. Robinson he knows how absolutely awful married life can be.

Life magazine noted that the film’s young male protagonist turns ‘from anti-hero … into a romantic hero’; the viewer is asked to sympathise with him although he remains ‘self-absorbed and shamelessly spoiled’ – ‘sentiment [thus] replaces [the] evenhanded toughness’ of the initial satire. Indeed, for this reviewer, the film’s satire did not only, or even primarily, target the world of the older generation but youth itself. According to Life, The Graduate manages ‘to satirize the alienated spirit of modern youth’ before eventually ‘selling out to the very spirit its creators intended to make fun of’.

Whereas the Life reviewer thus regretted the final shift from satire to sentimentality, other critics found The Graduate ‘moving precisely because [the film’s] hero passes from a premature maturity to an innocence regained, an idealism reconfirmed’, in the words of the Village Voice. According to Modern Screen, the viewer ‘will never forget [the film] as a beautifully touching tale of growing up.’

While a lot of this sounds very positive, or at worst like a balanced judgment, highlighting both strengths and weaknesses, there also were outright condemnations as in the New Leader review, which criticised the film for ‘oversimplification, overelaboration, eclecticism, obviousness, pretentiousness, and, especially in the penultimate section, sketchiness.’

Thus, reviewers – and also, probably, cinemagoers more generally – responded in very diverse ways to The Graduate. They had different understandings of what the film was trying to do, and came to different judgments about whether these were meaningful objectives, and about the extent to which the film managed to realise them, and about whether, therefore, it was any good or not.

Watching The Graduate (Again)

When (re-)viewing The Graduate today, it is perhaps best to approach it with an open mind about its objectives and achievements, rather than simply assuming that it is a classic movie about dissatisfied and rebellious youth, and true love. Despite its unassailable status and great familiarity, the film still has the power to confuse and disturb us, to raise many more questions than it answers.

Are we meant to sympathise with, or are we meant to take an increasingly critical stance towards, the film’s protagonist? After all, Benjamin’s reaction to being rejected by Elaine, when she realises that he had sex with her mother, is to stalk her, observing her from a distance around her home. He then announces to his parents that he is going to go to Berkeley, where Elaine is continuing her studies, and marry her, admitting that he has not in fact asked her and that she does not even like him. In Berkeley, he continues to stalk Elaine. And he does all this on the basis of having been together with her for a single evening (apart from the time they had known each other when they were much younger).

But are we even meant to take this story at face value, or are we to understand some, if not most, of it as Benjamin’s fantasy, as several reviewers suggested? In this context, the actually rather strange behaviour of both Mrs. Robinson (whose initial seduction scheme is very elaborate indeed) and Elaine (who repeatedly forgives him for his atrocious behaviour towards her) certainly feels more like a young man’s wish-fulfillment fantasy than realistic observation. On their first, and only, date Benjamin humiliates Elaine by taking her to a strip club; she starts crying and runs away. Yet, after a very brief apology, Benjamin kisses her – and she responds positively. A few hours later they seem to be in love.

When Benjamin surprises Elaine in Berkeley, she is, understandably (especially since we later find out that her mother told her that she was raped by Benjamin), initially quite reluctant to deal with him. But then she twice comes to the room he is renting (it is not at all clear how she could know where he stays), the second time while he is asleep, which makes her seem more like a dream apparition than a flesh-and-blood person. To Benjamin’s suggestion that they should get married, Elaine, quite unbelievably, responds by saying that she will think about it, although she is already engaged to another man. And, at the end, when her marriage ceremony has just been completed, she is still willing to run away with Benjamin. None of this is terribly convincing behaviour on her part, but it is in line with the kind of dramatic scenario a young man might construct in his head.

The film also has a lot of Freudian fun with establishing links between Mrs. Robinson and Benjamin’s mother. In several shots they are made to look quite similar (especially with regards to their hair style and hair colouring). And in the first conversation between Mr. Robinson and Benjamin the former points out that Benjamin is like a son to him, while also suggesting that he should have some sexual adventures, not knowing (or does he?) that taking this advice will push Benjamin into his wife’s arms. If Benjamin is like a son to Mr. Robinson, one would expect that Mrs. Robinson is like a mother to him.

Later on, in two consecutive shots, Benjamin repeats a line of dialogue (‘wait a minute’) which is first addressed to his mother who has queried him, while he was shaving in the bathroom, about his nightly activities, and then to Mrs. Robinson who he is about to have sex with. When Benjamin admits to Elaine that he is having an affair with a married woman, he tells her that this woman has a son, which does not, of course, apply to the Robinson family but to his own.

In addition to all this oedipal suggestiveness, one also has to wonder why Mr. Robinson is so insistent that Benjamin should go out with his daughter. From their first conversation it is clear that Mr. Robinson, perhaps mourning his own lost youth (we later find out that he had to marry Mrs. Robinson because of an unplanned pregnancy), thinks that at his age Benjamin should have as much sex as possible, presumably with as many partners as possible. Is this the kind of man a father would want for his daughter, especially when there is a strong suggestion that Mr. Robinson himself would like to be the kind of sexually active young male he encourages Benjamin to be?

Furthermore, one might ask whether Dustin Hoffman is ever really convincing as a supposedly highly articulate WASP (that is, White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) jock. Renata Adler was not the only critic who pointed out that Hoffman does not look like the ‘track star’ Benjamin is supposed to be, nor like a WASP; instead he looks like ‘a shy, inhibited intellectual (probably Jewish) who has never played on any team in all his life’. In other words, the film’s protagonist seems to have more in common with the Jewish actor who plays him than with the upper middle-class WASP character envisioned in the source novel and the screenplay.

This reminds us of the fact that the late 1960s were a period in which Jewish movie actors, who unlike most of their famous Jewish predecessors did neither anglicise their names, nor adjust their facial features with nose jobs, made a huge impact in Hollywood. Next to Dustin Hoffman, we could mention Barbra Streisand’s spectacular movie debut in Funny Girl (1968), a film in which she plays a Jewish Broadway wannabe (based on legendary comedienne and singer Fanny Brice) who becomes a star despite the fact that (almost) everyone tells her that she looks too odd, too Jewish. It is as if the Jewish director of The Graduate (birth name Michael Igor Peschkowsky), its Jewish lead actor and its Jewish co-writer Buck Henry (birth name Buck Henry Zuckerman) were playing a game with the audience, challenging them to confront a distinctly Jewish presence in the film’s WASPish world.

Then there is the blank slate of Hoffman’s face which dominates much of the film (often in close-up), and his character’s very vague declaration that he wants his future to be ‘different’. As one reviewer pointed out: ‘This is not a picture of the wild revolt of the hippies, but a tale of serious minded kids whose only cause for raised eyebrows is a constant search for the answer to “why?”’. But are we really meant to go along with Benjamin’s unspecific and very mild ‘revolt’, his initially directionless and then misguided existential quest?

Perhaps he suffers from clinical depression, which suppresses his emotions and renders him inarticulate and generally very passive, except for occasional manic outbursts of activity – mostly to do with running (to get to Elaine ahead of Mrs. Robinson who has threatened to tell her about their affair; to catch a bus on which Elaine rides through Berkeley; to get to her wedding in time) and fast driving (to the strip club on his night out with Elaine, and back and forth between Northern and Southern California in the final section of the film).

Or perhaps he does have a rich inner life, except that it only ever shows up in the Simon & Garfunkel songs that follow him throughout much of the film. Yet even the use of these songs is very odd, because they are repeated, in longer or shorter snippets, over and over again, with or without the lyrics being sung. Thus, ‘The Sound of Silence’ (perhaps a song evoking depression) is repeated during the first part of the film – from Benjamin’s arrival at Los Angeles airport to the moment when Elaine learns about his affair with her mother –, while ‘Scarborough Fair’ is played several times while Benjamin is stalking Elaine both in Los Angeles and in Berkeley, the song’s beauty and emotionality making Benjamin’s behaviour appear less sinister, and Elaine’s reaction less absurd, than it actually is.

Very strangely, the melody of ‘Mrs. Robinson’ is first being whistled (twice, on both occasions Benjamin appears on screen, although there is not a strong sense of him doing the actual whistling), before the song is played properly (once again accompanying shots of Benjamin), mostly without the lyrics. What is particularly strange is that all of this occurs at a time when Benjamin is focusing all of his attention on getting together with Elaine. Why does this song about her mother, which is redemptive (‘Jesus loves you more than you will know’) and indeed a kind of celebration (‘And here’s to you, Mrs. Robinson’), haunt him at this time?

Finally, there is the ending. What are we to make of it? There certainly is a moment of triumph, when Elaine runs out of the church after already having been wed to her tall, blond, extremely WASPish husband, and Benjamin manages to lock the door with a cross (an especially playful touch for all those who recognise Benjamin/Hoffman as Jewish) so that they can safely get away from their pursuers and board a bus.

But the long-held shot of them sitting at the back of the bus, initially with smiles on their faces and some acknowledgment of each other, gradually reveals the distance between them, their lack of connection, the process by which joy gives way to a sober evaluation of their situation, perhaps to doubt, even dread, about the future. Their difficult-to-read, rather blank expressions are juxtaposed with the final repetition of ‘The Sound of Silence’, which once again would appear to evoke a rather depressed state of mind: ‘Hello darkness, my old friend’.

Is this meant to be a happy ending? A tragic ending? Or what? As suggested earlier, when approaching the film today it is probably best to keep an open mind about such questions, considering all possibilities rather than rashly opting for only one of them. The film is most engaging and most powerful where we allow it to pull us simultaneously in different directions.

In Conclusion

While the original audience of The Graduate was mostly made up of young people who could see themselves reflected in Benjamin and Elaine, today the film is of equal interest to older people, looking back on their own youth or the turbulent period of the late 1960s or the overall arc of their lives. At the same time, the film speaks to today’s audiences, as much through the character of Mrs. Robinson as through the youthful leads, about timeless concerns: the burden of life’s many disappointments, the power of sexuality, the ideal (or fantasy) of true love – and about the magic of cinema itself.

It may be particularly poignant for us today, rather than experiencing the film’s story from Benjamin’s perspective, to look at the world through Mrs. Robinson’s eyes. As we learn in one of the film’s most moving, and in fact quite disturbing, scenes – in which Benjamin insists on having a proper conversation with Mrs. Robinson, instead of just having sex –, she got pregnant by accident as a college student, married a man she probably never loved, broke off her studies of art history and instead settled unhappily into motherhood and married life, learning to drown her sorrows in alcohol (if we take her earlier comment that she used to be an alcoholic seriously).

Throughout most of the film, Mrs. Robinson is displaying remarkable composure and the ability to take control of (almost) any situation she finds herself in – which makes her behaviour when, drenched from the rain and looking very bedraggled, she joins Benjamin in his car and tries to force him not to go out with her daughter ever again, all the more shocking.

Her previous stipulation that he should never date Elaine was probably motivated by the fear that her daughter would eventually find out about their affair and deeply resent her for it, but now she threatens Benjamin precisely with telling Elaine. Benjamin runs off to tell her himself before Mrs. Robinson can do so. After Elaine has realised the truth, the film’s emphasis shifts to Mrs. Robinson, who stands in a corner outside her daughter’s room, appearing very small, completely isolated and utterly devastated. Later on we see that Elaine does not even acknowledge her when she gets into her father’s car to be taken to Berkeley.

For many viewers today (and possibly even in the late 1960s), the scenes showing Mrs. Robinson’s vulnerability and her suffering linger in memory, movingly complemented by the redemptive and celebratory qualities of the film’s most memorable song: Here’s to you, Mrs. Robinson!

COMMENTS