Angelyne Narrowly Escapes Death

My film nearly became famous as the night that billboard queen Angelyne was crushed before a live audience.

For the premiere of my film Birds Die, I rented the movie theatre in the Hollyhock House, a Frank Lloyd Wright dwelling turned museum, in Barnsdale Park, perched on a hill at the crossroads of Vermont Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard. I went over early, with the cases of wine, the souvenir pens I’d had printed up, and all the food that my friend Natalie had spent the last two days slicing, chopping, and arranging into lovely colourful patterns on plastic trays.

I took the film up to Tom, the projectionist, so that he could check the sound levels. I was in a bit of a panic because Angelyne was due. I’d arranged for her to arrive by 7:00 p.m., which would give me enough time to stash both her and her pink Corvette away and not ruin the surprise.

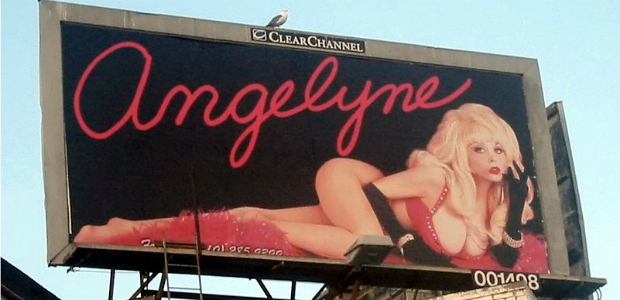

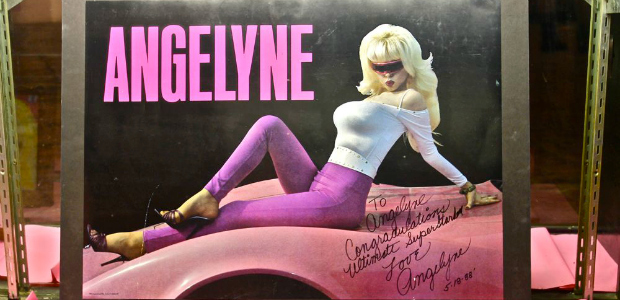

What is this Angelyne? An entity, an unexplained phenomenon, a Los Angeles myth: pert little nose, a shellacked fountain of blonde hair, a cartoonishly red and puckered mouth, and breasts like bowling balls. When I’d first arrived in Los Angeles, years before, I was fascinated by this unduly bosomed minx that stared down at us from billboards everywhere we went; her image—pouting behind sunglasses, draped over the hood of her pink car—could be seen when driving out of LAX, hovering over Laundromats in the Valley, bracketing Jiffy Lube and Pep Boys on Santa Monica and Sunset Boulevards, completely wrapping a four-storey building at Hollywood and Vine. She watched us when we were stuck in traffic, silent, scrutinizing, like a deity; we could place our own hopes and fears and wisdom onto the blank, bulbous canvas that was Angelyne. On all the hundreds of billboards there was no hint that she was advertising anything—and she wasn’t an actress as far as we knew, or a recording artist, or a politician—and her billboards had no other information than, simply, ‘Angelyne.’ She was part of our lives, and friends and I eagerly traded sightings. Everyone seemed to have one. Most claimed to have been stuck behind her on a freeway, or to have seen her pawing through the cantaloupes at Alpha Beta.

Needless to say I was a proud, pink-card-carrying member of the Angelyne Fan Club. I had called the number on the card a month before to see how much it would cost to have her appear. I thought it would help, add a sense of occasion to the evening, fluff the audience, as it were. And being slightly stage-fearful, I thought it might be a good idea to have such a Hollywood icon/travesty read my thank-yous for me.

‘$2000,’ said Scott, her manager. I explained the limited scale of both the evening and myself and politely declined. He called back the next day, his voice slightly more highly pitched as though constricted with desperation, and left a message saying that Angelyne would take a thousand. Being busy, I never got back to him, and the next day I had two messages from him, each with escalating…well, hunger. And the price kept going down. I finally returned his call. Angelyne would not only read the thank yous, but would pose by her car for photos after the screening. I wrote a check for $200 as a down payment.

As I paced backstage at the Barnsdale, I got a call from Scott. He said that Angelyne would be a little late. This didn’t bode well. The element of surprise (perhaps in this instance the element could be better described as shock) was what I wanted. Who would care if Angelyne read names from the stage when they had already seen her wandering around out on the lawn? I suggested to Scott he drop her off at the loading dock and then sneak away to park the car. He fearfully told me that no one drives Angelyne’s car except for Angelyne.

‘Oooooh,’ she said, ‘I just saw a dead bird yesterday. But I couldn’t relate to it because it, like, had no life in its body, and I, you know, I’m still alive.’ I begged her to tell the story to the audience.

As the screening drew near I ran between the lobby, the green room, and the loading dock, looking for her. Jogging through the theatre auditorium I saw Tom was playing the film. I noticed that the print was so dark it was almost black. Guests had already arrived. I ran into the lobby through thickening clots of people hanging around anxiously, drinking the wine, and up into the projection booth. Natalie asked me, ‘Should I serve the food now?’ I glanced around: people were reaching over the bar and peeling back the Saran wrap, pulling the hors d’oeuvres away by the handful.

‘Feed them now,’ I said. Placate the beast, for disaster was looming large. Up in the booth Tom said that the mirror in the projector was broken.

‘Do you have a spare?’ I asked.

‘Nope,’ he said. He was a nice man, an honest man; he wouldn’t look into my eyes, and his voice became barely audible with the guilt and the shame. His demeanour was betraying a gloom so profound I knew we were in very deep trouble.

‘Can you get one?’ I asked, ‘Can I get one? From Mole Richardson or Wooden Nickel…’ or any of the other equipment houses in Hollywood? We’d just made a movie. Catastrophes were commonplace, and running off to a 24-hour camera supplier or film warehouse was a matter of daily occurrence (we’d had to do it when we ran out of stock in Fillmore; we’d had to do it when we forgot the film magazines in Riverside; we’d had to do it when the generator exploded in Tujunga). Tom said that it wasn’t something that people kept in stock: a mirror usually lasted the lifetime of the projector. He said it would take at least a month and a half to order one. I walked down the steps and peeked at the crowd. People coming down the stairs had to stay on the stairs. The woman playing the African harp could barely be heard over the din. I couldn’t cancel, get all these people to come back, make Natalie slice up all the vegetables again. Get Angelyne again.

Tom asked if I had a video of the movie. Despondent, too panicked to be angry, I said ‘No.’ I had some Beta tapes back at home in Venice Beach, tapes we had used for mixing the soundtrack, but it would take over an hour to get there and back, and it was already five minutes after eight. Then I remembered that I did have some tapes, fifty of them, in the trunk of car, the copies I’d brought to give to the cast and crew. But I had planned to show a film. I could have shown a video, and shown it with better resolution and for a lot less money, at home.

A man approached and I thought he was going to ask me for spare change. I backed away and then he introduced himself as Scott, Angelyne’s manager. He told me that Angelyne was in the Museum Staff parking. She was my big surprise, and a lot of people had already arrived. And her car was extremely distinctive, being a pink Corvette with ‘Angelyne’ plates. I told him to drive to the loading dock and to meet me there. He left to get Angelyne, I ran to the loading dock. She drove the wrong way down the driveway, causing perplexity among my last arriving crew members. She manoeuvred in next to a police car that was already parked there. I was still dizzy from the news about the projector, and nervous about the throng of people, when Scott got out of the passenger’s seat of the Corvette. Angelyne stayed in the car. I leaned up to the windshield and squinted inside. She drew back. I welcomed her through the windshield with gesticulations and she rolled up her window and snapped the door locks. I yelled that there were some dressing rooms inside where she could be comfortable. She made frantic hand signals through the windshield at Scott, and Scott turned to me and asked, ‘Uh, did you have a check for us?’ I told him that I certainly did, but, seriously, wouldn’t she be more comfortable…

‘Angelyne needs to see the cheque.’

Oh.

I ran inside and got my chequebook. With great flourishes of the elbow, I signed the cheque. I handed it to Scott. He scrutinized it. Then he held it up to the windshield and Angelyne leaned forward. Satisfied, she unlocked her door and emerged.

‘I’m so tired. I don’t even want to be here,’ she said. The billboards hadn’t changed in twenty years, and even then they had not only been airbrushed but also over-exposed. Angelyne, in the flesh, was easily in her sixties. She looked me up and down, her crimson lips gnarled in a sneer. Her face was powdered completely white, her nose had been whittled so repeatedly that all that was left was a little piece of pared cartilage floating free in the concavity that was her sinus. Her arms, glimpsed from under her boa, were sticks with flaps. With laborious clomps she walked toward the loading dock. She told me that she might not stay for the screening, she was so exhausted. According to our agreement she was expected to not only stay for the screening, but to remain afterward and sign autographs. No doubt for an additional price per photograph.

I got her up the stairs of the loading dock where she promptly star-struck (star-bludgeoned might be more apt, considering how hard she worked at it) the security guard, who couldn’t break his gaze from her breasts, and Angelyne was more than happy to coo and shake them. Tom came backstage to tell me the crowd was large enough to push the envelope of health and safety regulations, and getting restless, and had wolfed down all of the Natalie’s cheese cubes. I told him to open the doors. I explained the new plan to Angelyne—she would simply introduce me, and I would say the thank yous (I’d grown apprehensive about allowing Angelyne too much leeway).

‘I’m tired. Isn’t there anywhere to sit?’ she whined. Tom said that we could put Angelyne on a stool, raise the screen to reveal her, then hit her with a spotlight. That way she wouldn’t have to move at all.

As we were waiting for the lights to flash—Tom’s signal—Angelyne said to no one in particular, ‘Why am I here? What’s this even for?’ I could’ve been asking her to introduce a bestiality convention, for all she cared, as long as she got a cheque. I told it was for a film called Birds Die.

‘Oooooh,’ she said, ‘I just saw a dead bird yesterday. But I couldn’t relate to it because it, like, had no life in its body, and I, you know, I’m still alive.’ I begged her to tell the story to the audience.

The lights flashed. I peaked through the curtains to watch the audience and, like a game-show host, I welcomed the audience to the world premiere of Birds Die and announced, as the screen rose, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the one and only Angelyne!’ The spotlight hit her and the audience gasped. After a moment of stunned, suspended time, they exploded in applause.

‘I’d like to introduce the director,’ she squeaked, giggling like a pin-up, ‘He’s not nervous at all!’ That was it. That was six hundred dollars worth of Angelyne. I walked out onto the stage and took the mic from her. I thanked her, and told the audience to ‘Give it up for Angelyne!’ Our arrangement had been that, after I took the mic, the screen would descend again, with me in front and Angelyne remaining seated until it came down and she could retire backstage. I started my speech, my five pages of gratitude, and I noticed that people were looking past me, concerned. Then they started shouting, ‘Look out, Angelyne, look out!’ I turned around and instead of staying seated Angelyne had decided to get up out of her chair and spin aimlessly. As she did so the screen continued to come down, all thousand pounds of it. I was about to lunge and shove her out of the way but luckily she sort of just spun away upstage as the screen hit the floor with a thud. My film nearly became famous as the night that Angelyne was crushed before a live audience.

COMMENTS