American Independence

During the Ides of the 1980s, all seemed lost for American cinema. It was the era when comic book heroes became our reality, incarnated in Sylvester Stallone and the uber-American Arnold Schwarzenegger. Real life characters had all but disappeared from cinema, relegated to painful nostalgia for the early 1970s. Stallone, Schwarzenegger, Jingoism, Steven Segal, Manichean politics, Hulk Hogan, Mr. T. Bleak days.

But then things changed. Stallone and Schwarzenegger got paunchy, Sly falling into what appears to be early onset Alzheimers (Rocky VI, at the age of 60?) and Arnold assuming his inevitable and true vocation as a Head of State, seemingly only fit now for Leni Refenstahl movies. But, sadly, she’s gone. As is his film career. Costner—a mercifully short blip—has fallen victim to his own self-importance and our short-lived indulgence, and Mel Gibson has ascended into the ether and has long been given enough rope…(his new movie filmed entirely in ancient Mayan…it’s going to be too delicious!)

Like a weed impossibly forging its way through a crack in the concrete, American independent cinema popped up and flourished. There was hope. There is hope. Even though the term Independent has been snatched up and soiled as just another brand by the accountant-run studios, there still remain the small voices of true filmmakers as well as the load of steaming horseshit that passes itself off as independent. Two recent movies represent the zenith and the nadir of the current state of American Independent film.

Riding in on the Tarantino Pimpmobile, Hostel is an affront to all that is decent. BBFC gave it an 18 ‘strong bloody violence, torture and strong sex’. What about warnings for idiot behavior? What about restrictions against gratuitous tilts-down to asses? What about offences to credulity (the man disposing of the corpses in the dungeon was a hunchback)?

I don’t mind a lingering, loving close-up of a drill bit with a little offal stuck to it when the little bits of meat belong to an obnoxious, jingoistic, self-righteous American bully. What I find far more morally offensive and dangerously imitable (the greatest concern of the BBFC, by the way) is the institutionalized frat boy arrogance and unblinking solipsism of these Americans abroad.

Hostel is the tale of Paxton and Josh, two American backpackers trekking through Eastern Europe and showing these former Iron Curtain countries how ugly an Ugly American can be. With episodes of adolescent geek fantasy (hot Slovakian underwear models clambering to have three-ways, dispensing Ecstasy from their hooker-like tongues), pervasive chauvinism (at one point Paxton rages at the people in the rural regions of their own countries because they won’t speak English), and fetishized violence (mere gore is no longer frightening or clever; it’s just gore), Hostel has all the appeal of a war in Iraq.

The xenophobia is rampant. The film is aggressively bigoted, the blameless Americans mocking, among other things, the fact that some European adults smoke (the most egregious of all moral sins, though they have no qualms about ingesting any drugs they can find and drinking until they puke), European circumcision practices, and Icelanders. Surely there must be some BBFC provisions against the mistreatment of Icelanders?

Oli is a character they meet up with in their travels and, mercifully for him, is the first one to die (which hardly seems justifiable when there were two perfectly good American assholes to kill). But not before he must suffer humiliations no country should (and no country—save an equanimous Scandinavian one—probably would) endure. Oli must not only paint a face on his buttocks and make it sing, he must repeat the pain-inducing attempt at a catchphrase, ‘I’m the king of swing!’

Apparently Eli Roth, the director, issued a formal apology to the Icelandic Minister of Culture for all the damage Hostel may cause to Iceland’s reputation. Which is fine, but what about the Germans, who are made to look like Dr. Mengele? Or the rampant Slovakophobia? All Slovakians were evil ruthless sadists, from the aforementioned hot underwear models to the desk clerks to the police to the imps on the streets. This actually was alarming considering the movie had been filmed in the Czech Republic at the great Barrandov Studios. The Czech and Slovaks used to share a country. It seemed a little petty.

Hostel presents a world view, in this shooting-fish-in-a-barrel crime ring, that Americans are worth more because they cost more than any other nationality. And why shouldn’t they? The lead character was tortured with an electric drill, had his hand chainsawed, and was truncheoned with a garden trowel, presumably filling him with holes. But, being American, he oddly suffers very little ill effect, include blood loss. Nothing can stop him from becoming a vigilante superhero and grabbing the firearms and killing the bad people, or foreigners, although that’s pretty much the same thing.

‘Welcome to your worst nightmare’ the posters proclaim. Indeed.

Junebug, directed by Phil Morrison, is not just a fish out of water story (though it is), nor is it just a mockery of Southern Christians (which would have been fine). It is a superb and very funny movie about the everyday emptiness that we try to ignore. The film benefits from what true independents must—a low budget. Without the possibility to throw bundles of money at problems in order to solve them (or 150 gallons of blood, as was the case with Hostel), they have nothing to fall back on but talent. Without the dazzle camouflage of special effects to plug up a bad script, films—like Junebug—need an excellent script. And excellent actors. There is nothing to hide behind.

Madeline (Embeth Davidtz) meets George (Alessandro Nivola) at an auction at her upscale art gallery in Chicago. It’s certainly love at first sight, but an instinctual love. Lust, in other words. But a gentle kind of lust, a considerate lust; the sex is kindly and constant, but there is little else besides sex. They don’t really know the geology of each other, just the topography. What they have in common is not shared backgrounds or shared interests or any sort of history; what they have in common is innate goodness and the fact that they love each other.

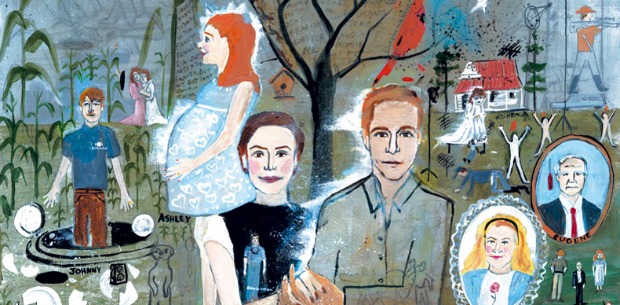

When they travel to North Carolina in order for Madeline to secure a reclusive folk artist for her gallery and finally meet George’s family—who don’t even know they’re married—their lack of mutual knowledge becomes abundantly and dangerously apparent. George’s rural world is very different from his urban one. Madeline’s facile charms and her ease with touching, compliments, and cheek-kissing—reflexive to her and therefore meaningless—are shocking to a family not accustomed to touching, not accustomed to being touched. As different as these two seem what all characters have vitally in common is isolation. No one can truly connect. For George’s mother, Peg (Celia Weston) and his father, Eugene (Scott Wilson) communication is just used for recrimination. Peg is locked in her routine of bitterness and suspicion, and Eugene spends the moments he’s not out buying cigarettes for his wife alone in his woodworking shop in the basement, so taciturn his face is practically ossified. George’s brother, Johnny (Ben McKenzie) is consumed by a wordless simmering hatred for his brother and the inevitable comparison he provides for Johnny’s own undreamed of potential. When Johnny needs to say something it’s with an elbow, a kick on the foot, unlike Madeline whose garrulous emotionalism bewilders and confuses her in-laws. Words are not weapons in the arsenals of these people, whose empathy and compassion have long since atrophied from lack of use. These characters are so isolated and lonely that epiphanies come not through reaching out but through recognition of each other’s emptiness. That’s enough. That’s communion, however feeble.

In the midst of it all is Ashley (Amy Adams), ebullient, empty-headed, heavily pregnant, guileless, and constantly chattering, seemingly without a filter between her impulse to speak and her mouth. She idolizes Madeline and is immune to the neglect and pain around her. She is the glue of innocence that holds the movie together.

These are not evil characters. They are not spiteful or mean. They are merely lost, swirling in lonely orbits around each other. They try to reach out, but they just don’t know how. Johnny tries to tape a programme on meerkats for Ashley—tries to perform the simplest of kindnesses—only to get it wrong and wind up screaming at her out of frustration at himself.

The film is rife with surprising moments of grace. At one point George is cajoled into singing a hymn at a church dinner. This could have been an easy joke—which such a moment usually would be in the hip and cynical world of indie filmmaking—but instead it becomes a touching moment of community, of grace, of surprise to the jaded Madeleine who didn’t even know her husband could sing, let alone remember the words to a Baptist hymn. We really don’t know much about people who share our lives, but do we know enough?

Junebug is aggressively non-Hollywood—there is little causality, only scenes of deepening character. There is also a boldness in the direction. Morrison stops all time to give us agonizing frames of inertia, empty landscapes, empty rooms, bereft of people, while the soundtrack itself becomes empty: no music, no atmosphere, just absolute silence. These are surprising and courageous moments—surprising in their naturalism and honesty, not the pat resolution of clichéd bathos reflexive in Hollywood movie.

This is a gentle, haunting, compassionate movie about the easy ways our lives can slowly become devastated: not with a bang, not even a whimper, but merely with silent neglect.

COMMENTS