The Ultimate Spectacle

Rather than dismissing Hollywood’s Science Fiction blockbusters as mere rollercoaster rides, we should take very seriously the opportunities they afford us for extraordinary experiences.

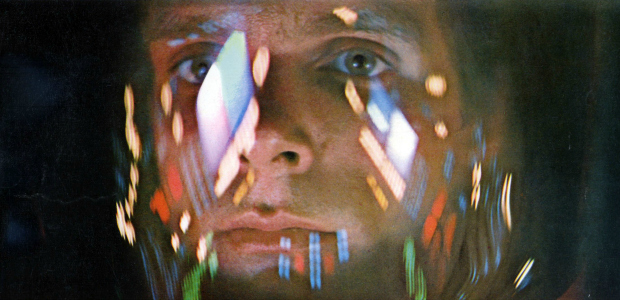

In July 1968, Stanley Kubrick received a letter from a fan of his recently released Science Fiction epic 2001: A Space Odyssey. Having seen the film several times, the fan described it as a ‘psychedelic rollercoaster’ of ‘such overpowering and breathtaking beauty that … I am at a loss at describing the feeling’.[1] Instead of commenting on the film’s story, characters and themes, and the thoughts and emotions these may generate, the letter emphasised the mind-expanding impact of beautiful images and virtual movement, and the impossibility to articulate this impact through words.

We might say that, first and foremost, this fan experienced the film as a spectacle. The term ‘spectacle’ is widely used by film critics, fans and scholars in discussions of Hollywood cinema in recent decades. In conjunction with the claim that many of Hollywood’s blockbuster productions are nothing more than ‘rollercoaster’ rides, describing such a film as a ‘spectacle’ is often intended as an expression of discontent; it implies that while the film may have an overwhelming impact on spectators, it does not have much to say, no great story to tell, no great themes to explore.

In this article I want to turn the usual critical deployment of ‘spectacle’ on its head by examining the word’s multiple meanings in considerable detail and then applying them to 2001 to show that ‘spectacle’ captures many of the outstanding qualities this film has been celebrated for. Indeed, one might go as far as saying that 2001 is the ultimate spectacle.

Before doing this, however, I want to comment on the enormous influence Kubrick’s film has exerted on subsequent Science Fiction cinema (such as the two films I have discussed in my previous two contributions to Pure Movies) [2] and also on Science Fiction scholarship (such as my own). I will then try to refute some of the common preconceptions about the film and its initial reception, before, finally, analysing its themes, form and style as well as its marketing and reception in terms of ‘spectacle’.

The Influence of 2001

2001 has a crucial place in the development of Science Fiction cinema. It has not only had a huge impact on regular cinemagoers such as the one cited at the beginning of this article but also on many people who later became filmmakers or film scholars with a particular interest in Science Fiction, and also on the American film industry as a whole.

The success of 2001 in the late 1960s – together with the success of Planet of the Apes which was released a few months after Kubrick’s film in 1968 – encouraged Hollywood to invest heavily in Science Fiction. Yet rather than focusing, like 2001, on space travel, encounters with extra-terrestrial intelligence and human evolution, the vast majority of Science Fiction productions during the next few years were critical explorations of future human societies on Earth, dealing with the impact of overpopulation, technologically enhanced political oppression, the aftermath of nuclear war etc. Several of these films focused on relations between humans and other earthly species (as in the four Planet of the Apes sequels released by 1973), or between humans and machines (as in Westworld [1973] and The Stepford Wives [1975]), the latter also being an important theme in 2001.

With the exception of Kubrick’s follow-up to 2001, A Clockwork Orange (1971), none of Hollywood’s many Science Fiction productions made it into annual chart of the ten top grossing movies in the United States before 1977.[3] But in that year, the two most successful films at the American box office were George Lucas’s Star Wars and Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the former breaking all existing box office records.

Lucas and Spielberg have acknowledged the formative influence of 2001 on their work.[4] Indeed, when Lucas first talked about his second Science Fiction project in 1974 (he had previously made the experimental, dystopian THX 1138 [1971]), he first referenced Flash Gordon and then described the planned film as ‘2001 meets James Bond, outer space and space ships flying in it.’[5]

Both Lucas and Spielberg had grown up with Science Fiction (in the form of novels, comic strips, films, movie serials and television series), and Spielberg had been particularly fond of Arthur C. Clarke’s work (Clarke was Kubrick’s main collaborator in the production of 2001).[6] When, following the release of Jaws in 1975, Spielberg focused all his energies on a film about UFOs and a climactic encounter with intelligent extra-terrestrial beings, 2001 was, in thematic terms, the most important cinematic reference point for such a project, and also the benchmark for achievements in the art of special effects, which is why Spielberg hired the effects specialist Douglas Trumbull who was most famous for his work on 2001.

In different ways, both Star Wars and Close Encounters built on 2001’s depiction of spacecraft and space travel, its epic scope and focus on events that have the power to change the direction of human history, and its exploration of the relationship between humans and aliens. They also shared with 2001 the spiritual, even religious view that there are higher, superhuman powers at work in the universe (the creators of the mysterious artifacts found in 2001; ‘the Force’ in Star Wars; angelic beings inhabiting the heavens in Close Encounters), and that these powers may enable us to be reborn – as a Star Child, a Jedi knight or one of the elect who ascends to heaven.

In the wake of the success of Star Wars and Close Encounters, there has been a significant change in Hollywood’s hit patterns. Many of Hollywood’s biggest hits since 1977, both in the United States and abroad, have been Science Fiction films.[7] These include a few Earth bound dystopias, typically dealing with a confrontation between humans and machines – as in the Terminator and Matrix films (since 1984 and 1999 respectively) -, and films about the potentially devastating impact of science and technology on life on Earth, as in War Games (1983), the Back to the Future trilogy (since 1985), the Jurassic Park films (since 1993), Godzilla (1998), The Day After Tomorrow (2004), I Am Legend (2007) and World War Z (2013).[8]

Yet, the biggest Science Fiction hits have been – much like 2001 – space adventures, and films about encounters with alien life forms (and machines) or with more highly evolved or genetically modified humans, on Earth or in space. These include the five Star Wars sequels and prequels (since 1980), the Star Trek and Alien movies (both since 1979), Contact (1997), Armaggedon (1998), Avatar (2009), and Gravity (2013), as well as the Superman films (since 1978), E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Cocoon (1985), Independence Day (1996), remakes of the Planet of the Apes films (2001 and 2011), Signs (2002), War of the Worlds (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), Marvel’s The Avengers (2012) and the Men in Black (since 1997) and Transformers movies (since 2007), plus the X-Men (since 2000) and Spider-Man films (since 2002).

Some of these films – notably Contact, Avatar and Gravity – would appear to have been influenced very directly by 2001, but all of them owe their existence to the fact that the commercial and critical success of Kubrick’s film inspired Lucas and Spielberg to make Star Wars and Close Encounters which in turn established Science Fiction as Hollywood’s dominant genre.

Indeed, 2001’s enormous influence on later filmmakers is evidenced by the fact that in the latest international Sight and Sound poll about the greatest movies of all time 2001 was voted second best by directors (in the critics’ poll it came in sixth place).[9] Several of the forty-two directors who listed 2001 as one of the ten best movies ever made noted the important role the film had played in their lives. Similarly, in a recent interview with the New Yorker, Lana (formerly Larry) Wachowski, of Matrix fame, remembered the extraordinary impact Kubrick’s film had had on her when she saw it as a ten-year-old: ‘2001 is one of the reasons I’m a filmmaker.’[10]

And then there is the case of James Cameron. His latest biographer writes: ‘The first time he considered film as a career was in 1968, when [at the age of 14] he staggered out of a Toronto movie theater showing 2001: A Space Odyssey. … he reeled outside into the sunlight, sat down on the curb, and threw up from the vertigo of the third act’s psychedelic trip sequence. “I didn’t know what to make of it”, he says. “It was really exciting intellectually, but mystifying and powerful visually. …” It was the moment Cameron went from being a fan of movies to wanting to make films himself.’[11]

Film scholars, especially those who came to specialise in Science Fiction, have also noted the formative experiences they have had with 2001. Thus, Christine Cornea’s preface for her 2007 book Science Fiction Cinema opens with an anecdote about listening, as a ten-year-old, to a conversation among adults which ‘revolved around their confusion over what was meant by the closing sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey … . This may have been the event that sparked my interest in the science fiction genre as I remember wishing I had seen the images that had caused so much debate.’[12]

Similarly, Scott Bukatman reports: ‘nothing will ever represent the future as strongly, to me, as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was the first film, I remember so vividly, that I ever attended alone, the friends and family of this nerdy eleven year old having little interest in either science fiction or experimental cinema.’[13] The film’s special effects made the future palpable for him and set him on a course which led to several books on Science Fiction cinema and special effects.

Watching 2001 as a teenager in the late 1970s was a formative experience for me as well. I had already been a fan of Science Fiction literature and cinema for several years, but it was my first encounter with 2001 – together with my first viewing of A Clockwork Orange around the same time – which made me think that perhaps here was something that I might want to study after finishing school, and, following some detours, this is exactly what I did, eventually turning my interest in movies into a career as a film scholar. However, I did not do any work on Kubrick until about ten years ago. Then I started to conduct research for a conference paper on 2001, which eventually led to a series of publications about the film.[14]

Before I summarise some of the results of my research, I want to highlight a few preconceptions that I had had – and had to overcome – when I started my work on 2001.

Misleading Preconceptions about 2001

If one has done any reading at all about 2001, one is likely to have acquired the following three preconceptions because they inform most of the academic and journalistic writing about 2001.

Number 1: 2001 was initially rejected by critics and audiences, but, a few months into its release in 1968, several critics had changed their minds and youth audiences started to embrace it vigorously, watching the film over and over again, often under the influence of drugs.

Number 2: With 2001, Kubrick set out to produce the most expensive avantgarde film ever made, departing radically from the conventions of mainstream filmmaking – which helps to explain why the film was initially rejected.

Number 3: 2001 is an expression of Kubrick’s deeply pessimistic worldview, insofar as its prehistoric sequence suggests that humanity is defined by the murderous use of tools, and its futuristic sequences depict a cold, dehumanised world in which the most emotional character is a computer (who turns murderous).

All of these preconceptions turn out to be wrong. Let’s take a look at the facts.

About preconception number 1: Upon its release in April 1968, 2001 was an instant success with the majority of critics and with a cross-section of the American population. It attracted family audiences as well as countercultural youth, and, with only minor breaks, stayed in cinemas well into the 1970s, becoming one of the top grossing films of all time at the US box office up to this point, while also coming to be regarded as one of the best films ever made.[15]

About preconception number 2: 2001 was in fact originally designed as a big budget blockbuster aimed at an all-inclusive mass audience by building on several of the most successful trends at the American box office in the 1950s and early 1960s, notably Cinerama travelogues, historical epics and Disney adventures (by contrast, Science Fiction films had very rarely been hits before 2001). Of course, the film also resonated strongly with topical interest in the space race across the 1960s.[16]

For most of its long production history, which began with a letter Kubrick wrote to leading Science Fiction author and science populariser Arthur C. Clarke in March 1964 suggesting that they work on a Science Fiction film (and novel) together, 2001 was meant to have a prologue consisting of interviews with scientists, extensive voice-over narration which explained what was going on, as well as a lot of explanatory dialogue. Only a few months before the release of 2001, Kubrick decided to remove all of these so that the film became very mysterious indeed – much like the alien artefacts in the film.[17]

The first of these artefacts had originally been designed as a transparent cube showing educational films to teach ape-like creatures (or hominids) about the use of tools. Already in April 1966, Kubrick expressed doubts about this idea – and, more generally, about the film’s excessive reliance on verbal explanations. In a letter to Clarke he wrote: ‘it seems to me that not showing the visions in the Cube helps prevent a kind of silly simplicity of which I think we are presently in danger.’[18] Eventually, the transparent cube became an opaque rectangular slab (or monolith), and Kubrick decided that the film itself should be opaque as well. 2001 was nevertheless marketed as an event movie for the whole family, and it was indeed embraced as such by the majority of cinemagoers who saw the film.[19]

About preconception number 3: Kubrick embarked on his collaboration with Clarke with a view of offering an optimistic alternative to the pessimism of his previous film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) which ends with the explosion of a nuclear ‘doomsday’ device that will destroy all life on the surface of the Earth. Kubrick was convinced that nuclear war was almost unavoidable. In a November 1963 interview with Cosmopolitan he stated: ‘The catch is that the inadvertent use of the bomb is, and will always be the greatest risk … If the system was safe for 99.99 per cent of the days of the year, given average luck, it would fail in thirty years.’[20]

So when Kubrick wrote to Clarke two months after Dr. Strangelove’s release in January 1964, the end of the world was still very much on his mind. One might say that, having produced a black comedy about how humanity will destroy itself on Earth, he was now looking into the heavens for a non-human force that could save humankind. Other people might call this force ‘God’, but for Kubrick it was extra-terrestrial intelligence.

In 2001 the extra-terrestrials act upon humankind through monoliths, which means that, by turning the film itself into a kind of monolith – a perfectly designed and beautiful, yet utterly opaque object -, Kubrick suggested that the film might have transformative powers with regards to its audience. Amazingly, many viewers, as we will see below, did experience the film precisely in this way.

I now want to start my examination of the spectacle of 2001 by turning to what is arguably the most authoritative source for the meanings of words in the English language.

The Spectacle of 2001

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word ‘spectacle’ can refer to something that is put on display, to the impression it makes on its audience and to a ‘means of seeing’ (as in spectacles or glasses). The thing that is put on display, the purpose of displaying it, the manner in which it is displayed and the impression it makes are all of a special quality.

The thing on display is often ‘striking or unusual’. The purpose for displaying it may be to provoke ‘curiosity or contempt’ or, alternatively, ‘marvel or admiration’. The manner of display tends to be ‘specially prepared or arranged’, ‘on a large scale’ and ‘public’. The audience’s response to this display is mainly to find it ‘impressive’, ‘interesting’, ‘agreeable’ and ‘imposing’ but it could also be full of contempt. More specifically, the word ‘spectacle’ is used in theatrical language to refer to a ‘piece of stage-display or pageantry, as contrasted with real drama’, which implies a negative judgment.

I will now sketch how the different semantic dimensions of ‘spectacle’ as outlined in the OED can be applied to the film to answer the following questions: What was so special about the film itself? What was its purpose, or rather: what was seen to be its purpose? How was it presented to the public? What impact did it have on its audience? How was it judged? We can even ask to what extent it changed people’s perception of the world, now seen, as it were, through new spectacles.

Film Form

2001 tells the story of the impact of alien monoliths, placed on Earth, on the Moon, near Jupiter and in a room light-years away, on hominids and human beings, bringing about two evolutionary leaps: the transition from pre-human to human, and from human to post-human. Thus, the film does not only cover a time span of four million years, but also marks the very beginning of human history and what may be the beginning of its end.

2001 tells this story in a cryptic manner. It is divided into four parts (five, if we take into account the fact that originally the third part was further divided by an intermission). These are separated by titles and/or drastic spatio-temporal shifts. Many of the causal connections between the four parts remain implicit and ambiguous as do the causal connections between many events within each part.

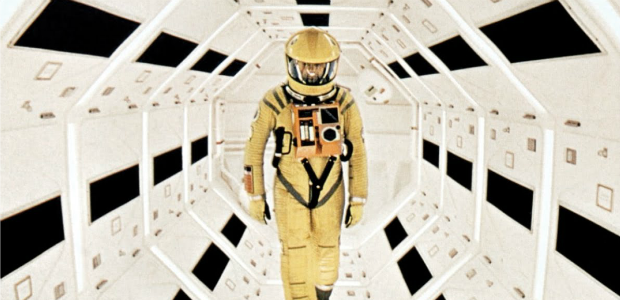

What is more, the film emphasises breathtaking vistas, the meticulous design and emphatic display of pre-historic or futuristic costumes, sets and locations, the leisurely delineation of physical movement, in particular the movement of vehicles and people in the weightlessness of space, and unexpected juxtapositions of images with classical or atonal music as well as sound effects and silence. All of this takes precedence over dialogue, expressive performance and character development.

In particular, during the space flight sequences, set design, camera angles and the actors’ positioning and movement aim to induce a feeling of disorientation or spatial disconnection in the spectator, whereby categories such as ‘up’ and ‘down’ are called into question. Similarly, the so-called ‘Star Gate’ sequence depicting an astronaut’s journey across space and time uses a range of techniques which create an often highly abstract impression of movement across, or of static displays of, celestial formations and alien ‘landscapes’, thus evoking the radical otherness of the astronaut’s experience.

There can be no doubt, then, that the film’s story as well as its form and style are indeed ‘striking and unusual’, to quote the OED’s definition of spectacle again.[21]

Purpose

When 2001 was released by MGM in April 1968, the public had long been prepared for it. What the trade press reported to be ‘the most extensive in-depth advertising, publicity and promotion campaign in [MGM’s] history’[22] had started three years earlier with the studio’s initial announcement of the project in February 1965.[23] This press release set the tone for the subsequent campaign, established the film’s main attractions, and allowed Kubrick, whose statements made up half of the text, to articulate his intentions for the film.

Kubrick described the planned film as ‘an epic story of adventure and exploration’ exploring ‘the infinite possibilities that space travel now opens to mankind’: ‘There will be dangers in space – but there also will be wonder, adventure, beauty, opportunity, and sources of knowledge that will transform our civilization, as the voyages of the Renaissance brought about the end of the Dark Ages.’ A key element of the film would be ‘the electrifying discovery of extra-terrestrial intelligence.’

As is clear from these quotations, variations of which would be repeated in marketing materials over the next few years, the film’s purpose was to provoke, in the words of the OED, ‘curiosity’, ‘marvel’ and ‘admiration’.[24]

Presentation

2001 was initially released as a Cinerama roadshow. By 1968 the Cinerama company had long ceased producing films in its original three-strip process which had launched the widescreen revolution of the early 1950s, using three cameras and three projectors. Instead the company now licensed the major studios to use the Cinerama label for particular single-strip 70mm productions which were guaranteed a release in Cinerama theatres with their huge curved screens.

The term ‘road-show’ refers to Hollywood’s dominant release strategy for big-budget movies in the 1950s and 1960s, whereby a film would first be shown at premium prices only in a few showcase cinemas (which, in the case of a Cinerama release, were mostly Cinerama theatres). A roadshow release aimed to have very long runs (in some cases for years) in its showcase cinemas, where it was presented with all the trappings of a night out at the ‘legitimate’ theatre: separate performances (instead of the normal practice of running films continuously throughout the day), advance bookings, an orchestral overture and an intermission.

In this way, a film such as 2001 became a special cultural event, which was, however, addressed not to the discerning few but to everybody who was willing and able to pay the higher ticket price. Later on, the film also received a general release at regular prices in regular cinemas, often while the initial roadshow engagements were still continuing. To some extent, even the film’s general release was infused with a sense of specialness by the prestige and grandeur of the initial roadshow presentation.

Clearly, then, the presentation of 2001 can be characterised, in the words of the OED, as being ‘specially prepared’ and ‘on a large scale’.

Impact

2001 was first released in only eleven Cinerama cinemas around the world at the beginning of April 1968. As a roadshow 2001 performed very well. It had an exceptionally large number of advance ticket sales before it was released, and by the end of the year, it had earned $8.5 million in rentals from only 125 cinemas in the US, and came eleventh in Variety’s list of the top grossing films of 1968. Once the film went on general release in 1969, on 35mm at regular prices in a large number of cinemas all over the US, it was able to reach audiences who had not previously had a chance to buy tickets for it, and by the end of 1969 it had added $6m to its rentals.[25]

The film’s impact on its viewers was so powerful that many felt compelled to send letters to Kubrick in which they reflected on their experiences. Given the film’s radical departures from Hollywood conventions, it is remarkable that most correspondents – men and women, young and old, cosmopolitan and provincial, art lovers and entertainment seekers – wrote very positively about it, and that many of them saw in it a message of hope.

Letter writers often discussed ‘birth’ and ‘rebirth’ among the film’s main themes, referencing especially the final transformation of an ageing astronaut into a foetus. According to one letter from May 1968, the film thus made a statement about the true purpose of the astronaut’s journey of exploration: ‘[his] discovery is not of some strange new world but of himself; the wisdom of age is his rebirth’.[26]

Several viewers felt that their own journey across the strange cinematic world of 2001 had strong parallels to that of the astronaut. Ultimately encountering themselves in the film, they were transformed by it, even reborn. ‘[2001] is constantly on my mind and has loosened some of my prejudices’, wrote one correspondent in April 1968, and then he asked: ‘how many times must I be born to realize what I am?’[27]

And a young woman from Ohio wrote to Kubrick to tell him that 2001 was ‘the greatest movie I have ever seen in my life. In fact it’s one of the greatest things that ever happened to me. … [2001 is] a hand reaching from destiny to help us on to better things. Mr. Kubrick, your movie – on me at least – has had the same effect as the monoliths pictured in the film had on the race of man.’

There is no doubt, then, that, in the words of the OED, viewers found 2001 to be ‘impressive’, ‘interesting’, and ‘imposing’. It is worth adding that most of them had this experience without consuming the hallucinogenic drugs which are so often associated with the film’s impact in the extensive literature about 2001.[28]

Judgement

In addition to the enthusiastic response of most regular cinemagoers, 2001 was well received by critics, except for a small number of leading New York reviewers whose work is often cited in support of the usual claims in the literature about the film’s initial critical rejection. In fact, Variety reported in June 1968 that ‘almost all out-of-town and foreign reviews have been excellent while those in N[ew] Y[ork] were generally downbeat.’[29]

Even in New York, though, there appears to have been a largely positive reception which escaped notice because good reviews were overshadowed by the attacks of a few high profile critics. A fifteen year old fan of the film was so concerned about the lack of appreciation in some quarters of the critical community that, as he wrote to Kubrick, he kept ‘a record of reviews that 2001 has received, mostly from New York publications. I am happy to announce that 33 are excellent, which is much more than the reviews that were not so good.’[30]

What is more, within a few years, 2001 came to be regarded as one of the best films of all time. This is evident in the most comprehensive survey of international critical opinion conducted every ten years since 1952 by the British film magazine Sight and Sound.[31] 2001 made it into the top 25 in 1972, and it was at number eleven in 1982, at number ten in 1992 and at number six in 2002 and 2012. Across these four decades, no other film made since the 1960s has consistently been as highly ranked as 2001.

Thus, to return to the OED’s theatrical definition of ‘spectacle’, critics did by no means condemn or belittle the ‘pageantry’ of 2001, when comparing it to ‘real drama’.

New Perceptions

Some of the people writing to Kubrick perceived 2001 as a radical break, and a new beginning, in film history. One of them claimed in May 1968: ‘2001 does not mark the growth of the art of the cinema; it is the birth of the cinema.’[32] This writer went on to outline the enormous, positive influence he thought this reborn cinema could exert on viewers and perhaps on society at large: ‘it is within the power of a film such as yours to give people a reason to go on living – to give them the courage to go on living. For 2001 implies much more than just an artistic revelation. On a philosophical level, it implies that if man is capable of this, he is capable of anything – anything rational and heroic and glorious and good. … How can man now be content to consider the trivial and mundane, when you have shown them a world full of stars, a world beyond the infinite?’

It would seem, then, that the experience of 2001 provided some viewers with a new ‘means of seeing’ the world, thus living up to the promise of the, in this context, least likely of the OED definitions of ‘spectacle’ quoted earlier.[33]

Conclusion

2001: A Space Odyssey has helped to change the lives of many people, and also the development of Hollywood cinema. While traditionally Science Fiction films had been marginal to Hollywood’s operations (they very rarely ranked highly in annual box office charts before 1968), the success of Kubrick’s film (together with that of Planet of the Apes) inspired filmmakers and studio executives to invest much more of their creativity and money in high profile Science Fiction productions, and starting with the release of Star Wars and Close Encounters in 1977 this investment generated unprecedented returns, attracting huge audiences around the globe.

Across many of Hollywood’s Science Fiction hits we find an emphasis not only on the main themes of 2001 – space travel, encounters with extra-terrestrial intelligence, human evolution, the relationship between humans and machines – but also on the perfection of special effects first achieved by 2001, and on the privileging, so characteristic of 2001, of spectacular sounds and images over story, character and dialogue; of fantastic settings and virtual movement over recognisable situations and narrative progression; of a sense of awe and wonder over more familiar emotions; of fundamental questions about life and the universe over the concerns of everyday life.

Through the mediation of Star Wars and Close Encounters, 2001 has thus helped Hollywood to increase its global impact by focusing on the alternative realities, spectacular attractions and big themes of Science Fiction, and in doing so to allow people everywhere to experience the world and themselves in new ways, and to ponder questions about future threats to, and opportunities for, all of humanity. Rather than dismissing Hollywood’s Science Fiction blockbusters as mere rollercoaster rides and empty spectacle, we should therefore take very seriously the opportunities they afford us for extraordinary sensual, emotional, intellectual and indeed spiritual experiences.

[1] Letter dated 20 July 1968, Wichita, Kansas. This letter – like all the other fan letters I quote in this article – is contained in folder SK/12/8/4 at the Stanley Kubrick Archive (SKA), University of the Arts London. The name of the author is known to me but to protect the anonymity of this and other correspondents, I will identify particular letters with reference to their date and the correspondents’ home town. Some of the letters are reprinted in Jerome Agel (ed.), The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, New York: Signet, 1970, pp. 171-92.

[2] See https://www.puremovies.co.uk/columns/avatar-environmental-politics-and-worldwide-success/, and https://www.puremovies.co.uk/columns/making-contact/.

[3] Cp. Peter Krämer, The New Hollywood: From Bonnie and Clyde to Star Wars, London: Wallflower Press, 2005, pp. 107-9.

[4] Cp. the documentary Standing on the Shoulders Of Kubrick: The Legacy of 2001, which is on the 2001 DVD in the 2007 Warner Bros. Kubrick box set.

[5] Larry Sturhahn, ‘The Filming of American Graffiti’, Filmmakers Newsletter, March 1974, pp. 19-27, reprinted in Sally Kline (ed.), George Lucas: Interviews, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999, p. 32.

[6] Joseph McBride, Steven Spielberg: A Biography, London: Faber and Faber, 1997, pp. 79, 105, 121, 161, 263.

[7] Cp. Peter Krämer, ‘Hollywood and Its Global Audiences: A Comparative Study of the Biggest Box Office Hits in the US and Outside the US Since the 1970s’, in Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst and Philippe Meers (eds), The New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, pp. 171-84.

[8] All the films mentioned in this paragraph were highly placed in the annual box office charts in the US; see http://www.boxofficemojo.com/yearly/. Most of them were also huge hits outside the US; see http://www.imdb.com/boxoffice/alltimegross?region=world-wide.

[9] James Bell, ‘Directors’ Poll’, Sight and Sound, September 2012, pp. 62-71.

[10] Aleksandar Hemon, ‘Beyond the Matrix’, New Yorker, 10 September 2012, http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2012/09/10/120901fa_fact_hemon?currentPage=all, last accessed 10 September 2012.

[11] Rebecca Keegan, The Futurist: The Life and Films of James Cameron, New York: Crown, 2009, pp. 10-11.

[12] Christine Cornea, Science Fiction Cinema: Between Fantasy and Reality, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007, p. ix.

[13] Scott Bukatman, Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Supermen in the 20th Century, Durham: Duke University Press, 2003, p. xi.

[14] Peter Krämer ‘“Dear Mr. Kubrick”: Audience Responses to 2001: A Space Odyssey in the Late 1960s’, Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, vol. 6, no. 2 (November 2009), http://www.participations.org/Volume%206/Issue%202/special/kramer.htm; Peter Krämer, 2001: A Space Odyssey (BFI Film Classics), London: British Film Institute, 2010; Peter Krämer, ‘”A film specially suitable for children”: The Marketing and Reception of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)’, in Bruce Babington and Noel Brown (eds), Family Films in Global Cinema: The World Beyond Disney, London: I. B. Tauris, forthcoming. Also see Peter Krämer, ‘An Introduction to 2001: A Space Odyssey(1968)’, ThinkingFilmCollective Blogspot, 5 November 2013, http://thinkingfilmcollective.blogspot.co.uk/.

[15] Krämer, 2001, pp. 90-3.

[16] Ibid., pp. 32-40.

[17] Ibid., pp. 41-54.

[18] Letter from Kubrick to Clarke, 11 April 1966, in folder SK/12/8/1/11, SKA.

[19] Krämer, ‘”Dear Mr. Kubrick”’.

[20] Lyn Tornabene, ‘The Bomb and Stanley Kubrick’, Cosmopolitan, November 1963, pp. 15-6.

[21] For a more extensive analysis of the film, see Krämer, 2001, pp. 55-85.

[22] ‘”Odyssey” on Time; O’Brien Comes Home’, Film and Television Daily, 27 March 1968, p. 3.

[23] ‘Stanley Kubrick to Film Journey Beyond the Stars in Cinerama for MGM’, 23 February 1965; a facsimile of this press release can be found in Piers Bizony, 2001: Filming the Future, London: Aurum, 2000, pp. 10-11.

[24] For a fuller discussion of the film’s marketing, see Krämer, ‘”A film specially suitable for children”’.

[25] Cp. Krämer, 2001, pp. 90-2.

[26] Letter dated 31 May 1968, Malibu.

[27] Letter dated 15 April 1968, Fort Lee, New Jersey.

[28] For a fuller discussion of audience responses to 2001, see Krämer, ‘”Dear Mr. Kubrick”’, and ‘”A film specially suitable for children”’.

[29] ‘2001 Gathers a Famous Fans File; Kubrick Reviews, Except in N.Y., Good’, Variety, 19 June 1968, p. 28.

[30] Letter dated 19 June 1968, Flushing, New York.

[31] Ian Christie, ‘Chronicle of a Fall Foretold’, Sight and Sound, September 2012, pp. 56-8.

[32] Letter dated 4 May 1968, Santa Monica.

[33] For a fuller discussion of audience responses, see 2001, first audiences essay, children, SFX

COMMENTS